LYNN HERSHMAN LEESON'S CYBORG DRAWINGS

Julia Heldt

“The subject in these drawings is not identifying itself via the mirror anymore, but has become one with the mirror, the screen, the interface, resulting in exposure and self-determination at once.”

INTRODUCTION: ZIPPING IN TO THE CYBORG

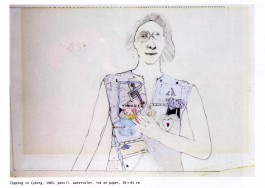

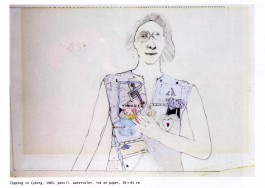

“made in U.S.A” is written in black, simple letters across the right side of the breast of a woman, drawn in pencil on a white piece of paper. (Un)zipping the vest with her left hand, a candid smile shows a row of small, regular teeth, and facing the viewer through her round glasses, the woman exposes her flat, white décolleté, (un)dressing herself. The vest itself displays a technical structure: lines resembling pipes or streets on a map are connected with a pump-like cylindrical construct, overlaid by a stomach-shaped organic structure in light pink. A heart in bright red, encircled by two bigger hearts, is linked with a pipe to the pump. The colour and structure of the forms are fading out towards the lower parts of the torso and the contouring lines of body and vest are blurred, loosened, blending into each other.

Suggested citation: Heldt, Julia (2019). “Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Cyborg Drawings.” In: Interface Critique Journal 2. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang.

DOI: 10.11588/ic.2019.2.66987

This article is released under a

Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).

Julia Heldt is an art historian and works as a curatorial and scientific trainee at the Haus der Kunst in Munich.

Fig. 1: Zipping in Cyborg, 1963.

The drawing Zipping in Cyborg (fig. 1), made by American artist Lynn Hershman Leeson (*1941, Cleveland, Ohio) in 1963 in pencil, watercolour and ink on paper, constitutes an early image of a then newly coined term: The Cyborg. It was introduced by scientist Manfred Clynes and physician Nathan Kline in the short text titled “Cyborgs and Space”, published in the September issue of Astronautics in 1960. Clynes and Kline propose the concept of the cyborg as an acronym for cybernetic organism, which is supposed to describe a “self-regulating man-machine system.”1 This system should serve as an augmentation of the human body making it able to survive in hostile environments during space travel. Growing out of the first years of the Cold War, the cyborg became a prominent figure connected with socio-cultural implications, redefining the being of humans in a world of new technology.2

One of the most famous interrogations of the cyborg term in relation to cultural and social paradigms is probably Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” from 1985.3 Haraway used the figure of the cyborg strictly metaphorically: To her, its image was a way to describe a cultural and social shift away from binary paradigms, emphasising its metaphorical quality, rather than its application in science. Before Haraway used the cyborg image for her feminist social theories and even before Clynes and Kline introduced the acronym, artists had been working with the concept of the human-machine fusion for a long time, for example Leonardo’s well known Vetruvian Man (1490), but especially since the beginning of the 20th century, when a growing involvement can be observed, with Dadaism and Futurism.4 Both Avant-garde groups subvert in their artworks the sovereignty and uniqueness of the human, by picturing their utopist visions of man-machine-fusions, blurring the boundary between human and technology, dismissing the sovereignty of the human and, at the same time, completing it with machines, referencing the century old reading of the human, and, especially, the woman, as inadequate and incomplete.5 Defining the production and use of tools as one of the earliest characteristics or skills of humans and their culture,6 the history of prostheses finds its technological equivalent in the cyborg, completing, augmenting or extending the human body and mind. Being situated on the unclear borders of human and technology, the cyborg works as an interface, through which the human can operate the technological – or through which the human can be technologically operated.

The focus of this essay is to look into the imagery of the cyborg that was produced around the time of the birth of the cyborg term. In a series of drawings, Lynn Hershman Leeson depicted mostly women7 in the tradition of human-machine fusions – especially Hannah Höch and Eva Hesse come to mind – and illustrates with these drawings social and cultural qualities of the cyborg. The female body, which is in those early drawings of Lynn Hershman Leeson often enough herself,8 is becoming an interface, being a surface of intersection, communicating mind and exterior, showing the direct influence of a societal shift and the way the female subject responds to this – be it with appropriation or shutting down. The flatness of the paper underlines the body as surface and becomes a kind of interface itself, a screen on which Hershman Leeson projects herself and her ideas. The cyborg, “born on the interface of automaton and autonomy”,9 is in these drawings too an interface between human and machine, aligning with Haraway’s theory through showing the possibility to dissolve boundaries and power structures and eventually creating a new way of thinking about the conception of the subject, that is mostly the female subject, in an evolving technological and digital world.

DRAWINGS ON SCREENS

Lynn Hershman Leeson divides her almost six decades spanning œuvre in two elementary stages: Before Computers (B.C.) and After Digital (A.D.). 10 She appropriates the terms that are being used to label years in the Julian and Gregorian calendars, indicating the years before Christ (BC) was born and after His Birth, anno domini (AD).11 By doing this, she puts not only the invention of the computer in direct relation to the birth of Christ, indicating that both are highly effective shifts in human history; but she also establishes a new history writing – one that is based on technological evolution, which shows a techno-centric worldview superseding the Christian worldview.

Hershman Leeson became known to be a vanguard artist in the use of technological and digital evolution in her works, though one of her most known works, the early performance The Dante Hotel (1973-1974), featuring two “life-size dolls with wax-heads”, which she modelled after her own face, placed in a hotel room, used technology only in a hidden way. The dolls, who made breathing sounds and moved slightly occasionally, are part of her Breathing Machines, a series of masks, she started making in 1965.12 Humanising these sculptural works by making them breathe and putting them in the hotel room, resembling real guests, Hershman Leeson blurs the boundaries between human and machine, fiction and reality – the installation was eventually shut down after a visitor called the police who suspected a crime scene at the hotel room.13

Around the same time as she began working on her Breathing Machines, Hershman Leeson addressed this topic in a series of drawings, which will be at the centre of the following essay. These drawings can be seen as the groundwork for her art, not only being the first she made that gained attention,14 but mostly because they are building the basis for her interrogation of the technological influence on the individual and society, as she came back to the image of the cyborg throughout her career, for example in works like the Phantom Limb Series (1985–ongoing), Seduction of a Cyborg (1994), Cyborg Series (1994–2006), Teknolust (2002), and others. She too continued to create works of art, which display a more distinct understanding and literal use of reciprocal interfaces, most prominently Lorna and Deep Contact (both 1984).15 In these early drawings, as I will show, a first understanding of the relation of women and technology is taking shape, establishing an abstract thinking of interfaces, less focused on user-device reciprocity and more on the literal meaning of interfaces as surfaces of intersection. Within those early works, she introduces an aesthetic that is both mechanics and technology related, but at the same time features forms and subjects that are highly idiosyncratic. The drawings are not accurate depictions of structures but speak of emotions and figuring out.

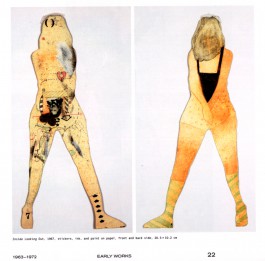

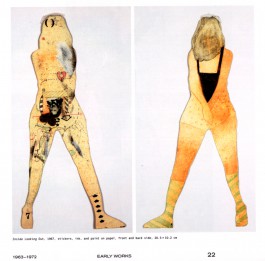

The double-sided work Inside Looking Out (fig. 2), from 1967 shows the front and back of a woman. Her body is not clearly outlined, though at some places yellow or green lines retrace the contours, still mostly bypassed by the translucent yellow fill colour. The back of her body is marked by her hair falling on her shoulders. Barely dressed, her roughly sketched hands, are held together over her bottom. Her skin colour is not even but shows in its present stage the age of the work itself. The rather simple back of her body is in no relation to what is pictured as her front. Without facial features, there are only abstract forms spread over her body which are stickers in the form of letters from an automated typesetting system. Hershman Leeson contrasts them with hand drawn parts, which can be found mostly on her lower torso, and includes technical drawings, such as fine arrows, dotted lines and cubes. Additionally, Hershman Leeson included heart shapes and drew simplified bones on her right upper leg. Having a phallic quality, the forms on her leg introduce a moment of sexuality to the drawing, further highlighted by a picture of an infant on her belly. The title of the work indicates that it is the inside of her body that we are looking at and that is looking at us. The drawing imagines the woman as a cyborg-like entity. The materialist approach to the female body opposes its essentialist truth as mother with a technologically altered anonymity. Inside Looking Out shows two ways of being a woman in a technological society, by appropriating it and by opposing it. Her crossed hands resemble a defensive motion, protecting her lower torso. Both parts of the work use their flatness: the first one creating a screen on which to present its interior to the exterior, the second one shutting itself out from any exterior, refusing communication.

Fig. 2: Inside Looking Out, 1967.

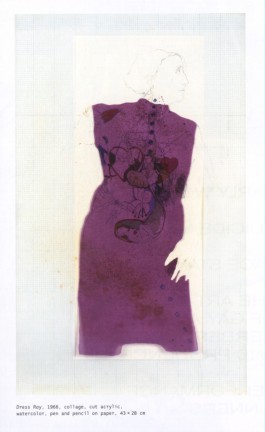

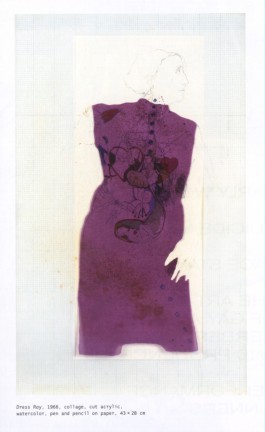

The blending of surface and interior, or putting the interior on the bodily surface is characteristic for Hershman Leeson’s early drawings, as can be seen in Dress Ray (1966, fig. 3), too. Using again collage techniques and drawing, Hershman Leeson here opens the flat space of the drawing and indicates spatial qualities, through the figure’s head turn to her right, while its title alludes to x-ray technology. Utilising the concept of the bodily surface, the skin and clothes, to examine the construction of the subject, she deploys historically and socially established features of women, but shifts their perception: The purple dress as feminine object becomes an x-ray screen or interface, being distinct from the white skinned female body. The dress like the skin, in Inside Looking Out, function as screens, representing an imagined biological and technical interior of the body, interspersed with emotional features with images of hearts and infants. In both works, the internal subject and the external technological society are intertwined in the cyborg figures.

Fig. 3: Dress Ray, 1966.

As with her Breathing Machines, Hershman Leeson makes use of the cultural topos of hiding or creating an identity, as Andreas Beitin notices:

„Beyond its sociocultural frame of reference, the mask as a second or alternative face can be inscribed in a terminological, etymological, epistemological, and not least technological line of development: face-mask-surface-interface-screen. Computer screens and tablet and smartphone displays, as today’s masks, offer an unlimited supply of electronic changes of identity.”16

And Hershman Leeson herself notes, that “Today, masks are interfaces that mutate through connectivity, merging the past and present through use.”17 Though Beitin focuses on newer works in his reading, creating an evolution in the use of masks, my point here is that the early works too show a conceptual understanding of interfaces as masks. By examining bodily surfaces, Hershman Leeson approaches the materialist notion of identity in relation to a technocratic society. This reading of the cyborg drawings as masked, questions the understanding of them as a projection of the interior, that I will discuss further along, or a looking in to the interior and rather proposes of them to be read as a way of superficial adaption to a new technological society. That the human has always been in need of adaption to its exterior and the materialist understanding of the cyborg as alteration and augmentation of the organism that is the human body will be the focus of the following chapter, taking into consideration the social and individual implications, especially on women, which this materialist reading of the cyborg can have.

THE INSUFFICIENT HUMAN

When in 1964, Herbert Marshall McLuhan wrote his iconic words, “the medium is the message”, he substituted them with the limitation that “[t]his is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium – that is, of any extension of ourselves – result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.”18 McLuhan, by introducing the reflexivity of technology and media into the social and personal conditions of humans, defines the media in the quoted insertion as an “extension of ourselves.”

The image of media as an extension of the human, or as McLuhan writes in the subtitle of the same book, “The Extensions of Man”, is based on an anthropocentric world view. Aligned with this, Ernst Kapp in his “Grundlinien einer Philosophie der Technik” (1877) traced the reading of tools as an extension of the body, based on the etymology of the Greek word organon, which means limb, its afterimage, the tool and even the material of which the tool is made.19 Kapp describes the history of civilisation as a history of labour and thereby drafts a materialist reading of society, describing human nature as one which always first creates his/her own culture. Unlike animals who survive because of their instincts, humans are, according to Kapp, in need of science and artificial creation.20 He goes on to describe the term “Projection”, which is in itself a mode of extension. Kapp uses the term Projection to explain the relations of emotions towards exterior things and the creation of imaginations.21 This metaphorical or imaginative reading of Projection adds a theoretical understanding of the extension of the human to the physical one, which tools stand for. Kapp’s imaginative and materialist extension of the human body and mind finds its equivalent in the reading of the cyborg figure, that I am discussing here. Augmenting the human body and mind, as Clynes and Kline imagined,22 the cyborg functions as the postmodernist tool extending the subject. Though the term Projection signals a one-way mode of communication, it functions as an interface too. That the cyborgised interfaces in Hershman Leeson’s drawings function as masks, a way not only to adapt to the exterior by superficially reflecting it, but also as possibly hiding the interior, or, at least communicating a mediated, altered or limited persona through it, relates to Kapp’s idea of Projection.

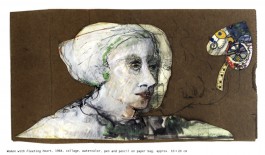

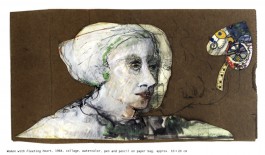

Another example for this is Woman with Fleeting Heart (1964, fig. 4), depicting a woman’s head to which a heart shaped structure is attached by a chord, being prostheses and projection at the same time, the heart appears outsourced of the woman’s body, her glance absent and behind her a shadow that is more of a doubling. The shadow might in this case indicate a narrative time, a before and after, dissolving the flatness of the paper screen or another kind of simplifying mask, layered before her own more profoundly sketched face. In this case, the cord connecting heart and woman signifies the interface, a string of intersection rather than a surface. That the heart in contrast to the woman’s body, at least what we see of it, is highly marked by technological drawings, more detailed than the contours of the woman herself, and her melancholic almost empty gaze, implies a technological augmentation of an insufficient woman, who became incomplete through almost losing her heart.

Fig. 4: Woman with Fleeting Heart, 1964.

This notion of incompleteness, physiologically or socially, is also found in the techno-philosophical concept of Kapp and his followers. It is not just that humans need augmentation to survive in space, like the cyborg figure, but according to some conservative cultural anthropologists they also need it to survive in general. The human need for augmentation is exemplified by Arnold Gehlen’s term of the “Mängelwesen”, a deficient being, which he coined in his 1940 published work “Der Mensch: Seine Natur und seine Stellung in der Welt”. Gehlen advocates the importance of tools, as they are the defining element of humanity: Only where there were tools in history, there were beings defined as human. The need for these tools is explained by Gehlen through the incompleteness of the human body. Lacking certain organs and instincts, the human could not have survived without creating tools and augmenting his surroundings intelligently.23 Like Kapp, who also describes humanity’s history as a history of tools, Gehlen describes tools and their subsequent technology, as prostheses for humans. He uses the term Mängelwesen as an immutability of the conditio humana, demanding the human trait to learn, to adapt to new situations to be stabilised,24 which can be achieved through use of technology. That Gehlen’s reading of the human as Mängelwesen – a term originally introduced by Johann Gottfried Herder25 – and his subsequent demand for strong institutions, meaning regulatory systems should be seen critically is underlined by his historical background as a member of the NSDAP and his conservative “Philosophy of Institutions” from the after-war years, which found a strong opponent in the Frankfurt School, namely the critical theory of Jürgen Habermas.26 Though the cyborg figure as such evidently functions as just what Gehlen demanded – a tool to augment the human body and mind – it’s cultural appropriation of the after war years, most prominently Donna Haraway’s metaphorical use of it but also Hershman Leeson’s more literal use, oppose Gehlen’s techno-philosophical approach, by underlining the individualistic quality of the cyborg image. This is especially evident in their use of female cyborg images and their possibility to (de)construct their selves.

THE CYBORG AS COMPLETION OF THE INSUFFICIENT WOMAN

While Clynes and Kline had a specific idea of the cyborg in mind, a control system that can be used for those travelling to space, the cyborg concept that is advocated by Lynn Hershman Leeson and Donna Haraway, demands a structural understanding. Haraway’s cyborg concept disrupts established power structures and institutions, as she summarises towards the end of her Manifesto:

“To recapitulate, certain dualisms have all been systemic to the logics and practices of domination of women, people of color, nature, workers, animals – in short, domination of all constituted as others, whose task is to mirror the self.”27

Dissolving those dualisms, the cyborg figure questions power relations those dualisms and social institutions have established.

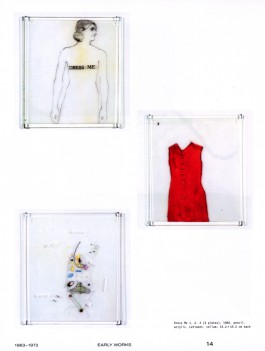

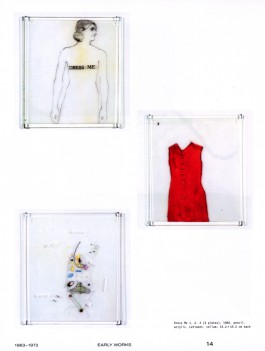

While Haraway’s cyborg remains completely metaphorical, Hershman Leeson deploys a subversion of power structures in her cyborg drawings, that is of a more literal quality. In the three-part work Dress Me (fig. 5), from 1965, she shows a woman in three stages. In the first, the woman’s body remains plain, outlined only by black pencil strokes. Bold letters read “DRESS ME” across her chest. Gazing to her left, she seems to be expecting someone following her invitation, resembling paper dolls, that children can dress in various outfits. The second part of the work consists of a bright red drawing of a dress, ready to be laid over the woman-figure.

Fig. 5: Dress Me 1, 2, 3 (3 plates), 1965.

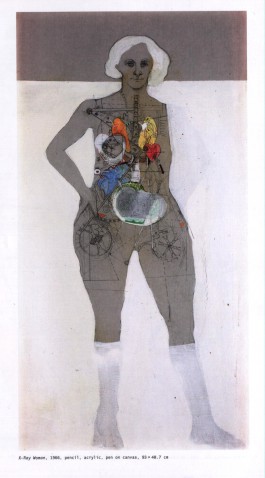

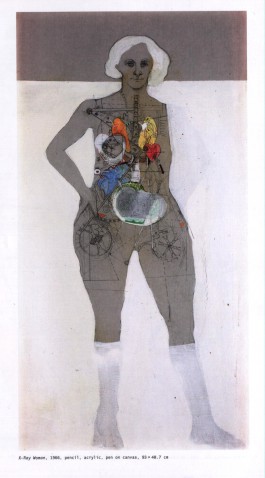

The third part shows the interior of the woman, similar to the other works already discussed and X-Ray Woman (fig. 6), mechanical drawings and figures cover an area in the shape of a torso, missing limbs. As Kerry Doran writes, the two outfits are options that determine the woman’s self – at least for that day –:

“She longingly looks toward her two garment options: an average looking coral frock or a diagram of parts, words, and pieces, appearing simultaneously deconstructed and reassembled, as though taking in the outside forces that seek to define a woman wearing a dress in the world […].”28

Fig. 6: X-Ray Woman, 1966.

Simultaneously depicting the woman as a doll, who is subjected by the ones who dress her and as an individual that can create her own reality by her choice of clothes, Hershman Leeson’s woman in this drawing is still an insufficient self, “longing” for augmentation, be it through clothes that make her herself or an outside power that imposes their opinions on her, thereby situating the woman in the context of an evolution of independence of the years the work was made.

The concept of the Mängelwesen can be seen as a predecessor-figure for what came to be the cyborgised human.29 As humans needed tools to establish their culture and ensure their survival, they took on to need technology to do the same, which resulted in the technologically augmented human. Completed and improved not just by technological tools like cell phones and the computer but also by medical tools, which establish the human beyond its natural transiency.30 This emancipatory quality of the cyborgised human towards nature, is the core figure of the post- and trans-humanist theories, and it comprises the image of a New Human, in which human and machine create the interface that is the augmented human body.31 This yields into a freeing state for the human, who is not subjected by nature anymore, as trans-humanist Fereidoun M. Esfandiary writes: “So as long as there is death no one is free.”32 As transhumanism wishes the human to not just become one with machines, but outsource mind and memory into computers, to abolish death and be able to live forever within the cyberspace,33 the cyborg figures of the 1960s are early positivist images of the wish to overcome natural and social preconditions and establish a self-determined life and self. Hershman Leeson’s images speak of these ideas and narrow them down to the position of women in 1960s USA. Her feminist approach to undermine essentialist notions of what it is to be woman was continued by Haraway, as she too uses the human-machine fusion to dismantle human and female preconditions, social as well as natural. In contrast to this, Gehlen does not describe the possibility of technology to liberate humanity from its natural burdens, but rather sees it in its culture creating way, to establish rules and paradigms in the form of strong institutions, rather than to overcome them.

The cyborg was intended to augment the human. Hershman Leeson uses the cyborg image in her works to question the very being of the Human, or in most cases, women in the form of “feminine machines.”34 She thereby inverses the implication of power structures that Gehlen sees in technology and dissolves them, by dissolving the constitution of the female body, opening it up to interrogation via x-ray and including the mechanical into its essentialist nature. The depicted women openly wear their relation to the exterior in their bodies, becoming themselves interfaces. In the case of Dress Me, the human body as interface, stands for the possibility to self-government and emancipation. This positivist reading, though, needs to be seen ambivalently: Women emancipating themselves were just recently oppressed women; their empty faces and eyes or the isolation of the backside of Inside Looking Out, for example, speak of this ambivalence towards the technological influence on the individual.

THE CYBORG AS EXTENSION OF THE MIND

A similar conservative or pessimist point of view as Gehlen’s is represented by Jean Baudrillard in a lecture held at the 1988 conference “Philosophie der neuen Technologie” in Linz, Austria. Baudrillard claims in his subsequent essay “Videowelt und fraktales Subjekt” that the human is only living as a “fractal subject”, a subject broken into pieces, more and more abandoning its social skills and only differing from machines in its ability to feel “passion”.35 According to Baudrillard, the human as a subject becomes increasingly insensitive and is only able to live and feel because of technological prostheses.

Following McLuhan’s theory of the extension of the human through technology, Baudrillard describes the brain in separation of the body, the body as an excess of the mind.36 Baudrillard adapts the Cartesian theorem of the mind-body-dualism, in which Descartes describes the human as a machine as well,37 and transcribes it to the postmodern age. In his idea of the “fractal subject”, the mind is split into parts, an idea that can be seen in relation to the cyborg, in which single body parts are individualised and outsourced or replaced, as they become subject of augmentation in Clynes and Kline’s proposal, or in Hershman Leeson’s view, splitting up the body in flattened front and back and screening its interior with mind and heart being external. The material body becomes the interface, communicating between mind and society, thereby detaching itself from the first. The divisibility of the human body in view of technology is present in another series of works by Hershman Leeson titled Phantom Limbs (1985–1987), that consists of photographs of women whose body parts, such as their heads, legs or arms are replaced by cameras, screens or sockets and that Genevieve Quick described as “spectral bod[ies].”38

Like Baudrillard, Haraway takes part in the question of mind-body-separation, as Gavin Rae suggests that her “thinking is profoundly, if implicitly, influenced by Heidegger’s critique of the binary oppositions underpinning Cartesian anthropocentrism.”39 Rae summarises Haraway’s endeavour with her questioning of “what it is to be ‘human’”40. Opposing feminist essentialism, she uses the cyborg imagery to dissolve body-mind boundaries as well as many other dichotomies.41 Her positivistic approach contrasts with Baudrillard, who considers the dissolving of the human entity through technology a loss of sociality, of empathy towards the self and others. Baudrillard goes on to disagree with McLuhan, who too sees the extension of the human through technology as potential and claims that the parts of the human body, including the brain, have separated themselves from the human and surrounding it “eccentrically” instead of “concentrically”. The parts of the body, that Baudrillard thinks of as prostheses, are highly influenced by the technology surrounding them, even becoming one with it, viewing human and machine as inseparable.42

Baudrillard’s negative evaluation is mostly based on the shift he sees in the self-identification of the subject and the bodily screen as interface, claiming, that the “video stage has superseded the mirror stage.”43 The subject only views and communicates itself via the mediated medium of the screen dominated by superficiality and meaninglessness, instead of the immediacy of the mirror. According to Baudrillard, the screen cannot be used for an active analysis of one’s own, but only as a self-monitoring tool in an “instantaneous and superficial refraction”.44 The “refraction” of the self-image describes a shifted view of one’s self, caused by the medium. Baudrillard states that

“we once used to live in the imaginary of the mirror, the divisiveness and the I-scene, the alterity and the alienation. Today we are living in the imaginary of the screen, the interface and the multiplicity, communication and network.”45

The subject, in Baudrillard’s pessimist understanding of technology, is dominated by the perception through screens and interfaces, without being able to differentiate between singular identities, the subject is only one part of a bigger picture. The identification of the self, that Baudrillard seems to be missing in the “videoworld”, is of similar complications as the identification of Hershman Leeson’s cyborg drawings, as they too perceive and project only a mediated version of themselves through their bodily screens.

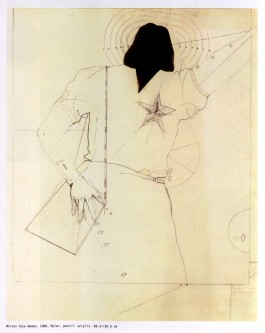

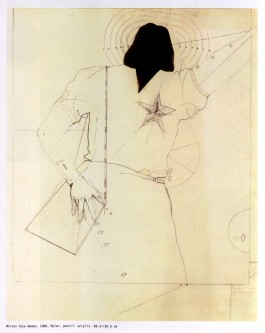

The identification of one’s self through the view of others is what Hershman Leeson addresses in her drawing Mirror Face Woman (1966, fig. 7) too, as Charles Desmarais describes the depicted woman as someone, “who exists as a reflection of others who is alive only on the viewer’s terms.”46 Hershman Leeson’s mirror-faced figure is like those other early drawings marked by technical details. Her broad shoulders and straight uplifted left arm indicate strength that contrasts the interpretation of her mirrored face by Desmarais. Subverting the negative interpretation of the superficiality of her mirrored face, it can too function as a shield. Mirroring the exterior, shielding her mind of it, Mirror Face Woman exists on the verge of being independent and defined by others, at the same time declining a communication, throwing the perceiver back at herself, becoming an interface in the meaning of a mask only in a one-way direction.

Fig. 7: Mirror Face Woman, 1966.

CONCLUSION

Created in the 1960s, Lynn Hershman Leeson’s cyborg drawings came to life amidst an emancipatory movement. With the means of technology, her figures question the essence of being – being female, that is. While Clynes and Kline thought of the cyborg as a mechanism that should “leav[e] man free to explore, to create, to think, and to feel”47, Hershman Leeson adopts the cyborg image to create her own figures of emancipation, that are not always strong and self-sufficient but fractal identities influenced from the outside. Like with her Dante Hotel, she creates her own images of identity and reality – like she continued to do within the parallel reality of Second Live and the screen.48 The cyborg drawings stand at the beginning of that œuvre, using the body as a screen to project seemingly subjective perceptions of the self, though not completely independent from the technological society. Anticipating the outsourcing of the human mind through the digital, she shows the heart of her Women with fleeting heart full of technology to be outside of her body, leaving it behind, attached only by a cable, reminding us today of the those who experience love and life within the digital world.

The singular positioning of the figures in time and space-less places establish the cyborg figures as fantasies, becoming tangible only in the realm of the paper as screen. Using the body as a screen too, her cyborg figures are not just interfaces between human and machine, but also predecessors of the interface of the computer, reciprocal systems that Hershman Leeson used in later works, communicating between interior mind and exterior society. In the computer’s Foucauldian Heterotopia49 of fiction and reality, the subject can create a self, screened on the surface of the computer just as the fictionalised inside of Hershman Leeson’s cyborg drawings. Projecting the mental inside to the social outside the cyborg images discussed, create a materialist notion of identity creation that is defined by technical and mechanical structures but stays imaginary. The subject in these drawings is not identifying itself via the mirror anymore, but has become one with the mirror, the screen, the interface, resulting in exposure and self-determination at once. The screen has become a new kind of mask, like McLuhan proposed, through which the subject communicates, and which is increasingly dislocated in the digital world.50

The women in Hershman Leeson’s drawings, with whom she identified with,51 are shaped by an effort to figure the self out. Just as Baudrillard viewed the technological self as fractal, as alienated parts, it is what Hershman Leeson’s drawings propose as a possibility. Being able to construct the self and the body with single parts and forms, she illustrates in her drawings a notion of emancipation as well as insecurity. It is not always a strong, self-assured woman that the drawings allude to, but often enough a woman marked by social structures to which she opens up. In their fragility referencing the notion of the insufficient human and woman, the cyborg drawings and the cyborg metaphor propose a solution that is not marked by totality but that is itself constructed. It is a figure marked by ambivalence, figuring out and being in-between.

Having not been able to completely overcome nature’s burdens, as post- and transhumanism would wish for, the cyborg drawings by Hershman Leeson are still marked by an essentialist conception of women marked by emotion and their biological functions. The loosened quality of her strokes can be seen as her artistic means of describing the freeing but also unsettling quality of the cyborg – which is contrary to the one proposed by Clynes and Kline or the social implications Gehlen described for the use of technology. Rather, her cyborg images aim to free the depicted subjects of social and cultural anticipations, allowing them to develop an individual material and subjective versatile structure and allowing communication between interior and society.

Moving on the edge of material and subjective, the cyborgs in Hershman Leeson’s early works illustrate a possible alienation of body and soul. This separation is congruent with our understanding of the cyborg within the realms of cyberspace: Through the concept of the interface, the cyborgised subject is able to overcome the reality of her own body and move over into the Heterotopic world of the screen, being their own perception, their own reality. This shows the possibility of the cyborg to free and extend the human not only outwards, as a physical prosthesis, but inwards too, to create and hide or expose a self and own reality, independent of established social and political structures. Using mechanical or technological prostheses to do so, the cyborg image remains open to include the exterior into the human, its body and self – just as the computer or cell phone can be considered as prostheses, as parts of ourselves, making all of us cyborgs.

References

Balsamo, Anne, Technologies of the Gendered Body. Reading Cyborg Women. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997).

Baudrillard, Jean, Videowelt und fraktales Subjekt, in: Aisthesis. Wahrnehmung heute oder Perspektiven einer anderen Ästhetik. Essays, ed. Karlheinz Barck, (Leipzig: Reclam, 1990), pp. 252–264.

Biro, Matthew, The Dada Cyborg. Visions of the new Human in Weimar Berlin (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

Black, Hannah, Lynn Hershman Leeson at Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie. Art in America (April 27, 2015), http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/reviews/lynn-hershman-leeson/, access: September 12, 2018, 1.30pm.

Bleier, Ruth, Science and Gender: A Critique of Biology and Its Theories on Women (New York: Pergamon Press, 1984).

Bloom, Harold, On the Origin and Evolution of Human Culture. American Scientist 51, no. 1 (March 1963), pp. 32–47

Clynes, Manfred, and Nathan Kline, Cyborgs and Space. Astronautics (September 1960), pp. 26–27 and pp. 74–76.

Desmarais, Charles, Lynn Hershman Leeson: Myths and machines at YBCA. SFGate (February 10, 2017), http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Lynn-Hershman-Leeson-Myths-and-machines-at-YBCA-10923873.php, access: October 12, 2018, 10.30am.

Doran, Kerry, Cyborg Origins: Lynn Hershman Leeson at Bridget Donahue. Rhizome, March 19, 2015. http://rhizome.org/editorial/2015/mar/19/lynn-hershman-leeson-origins-species, access: September 30, 2018, 4.30pm.

Downey, Gary Lee, Joseph Dumit and Sarah Williams, Cyborg Anthropology. Cultural Anthropology 10, no. 2 (May 1995), pp. 264–269.

Gehlen, Arnold, Urmensch und Spätkultur. Philosophische Ergebnisse und Aussagen, (Bonn: Athenäum-Verlag, 1956).

Gehlen, Arnold, Die Seele im technischen Zeitalter. Sozialpsychologische Probleme in der industriellen Gesellschaft, (Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann, 2007).

Gray, Chris Hables, ed., The Cyborg Handbook, (New York: Routledge, 1995).

Greenberger, Alex, A New Future from the Passed: Lynn Hershman Leeson Comes into Her Own After 50 Years of Prophetic Work. Artnews (March 28, 2017), http://www.artnews.com/2017/03/28/a-new-future-from-the-passed-lynn-hershman-leeson-comes-into-her-own-after-50-years-of-prophetic-work/, access: October 12, 2018, 10:15am.

Habermas, Jürgen, Anthropologie, in: Philosophie, ed. Alwin Diemer and Ivo Frenzel (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Lexikon, 1958), p. 33.

Haraway, Donna, Primate Visions. Race, Gender and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 1989).

Haraway, Donna, A Cyborg Manifesto. Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s, in: The Cybercultures Reader, ed. David Bell and Barbara M. Kennedy (New York and London: Routledge, 2000), pp. 291–324.

Hulten, Pontus, The Machine. As seen at the End of the Mechanical Age (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1968).

John, Jennifer, Lynn Hershman ‚Roberta Breitmore.’ http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/werke/roberta-breitmore/#reiter, access: October 9, 2018, 12.30am.

Kapp, Ernst, Grundlinien einer Philosophie der Technik. Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Cultur aus neuen Gesichtspunkten (Braunschweig: G. Westermann, 1877), https://archive.org/details/grundlinieneine00kappgoog, access: October 12, 2018, 10.30am.

Krüger, Oliver, Die Vervollkommnung des Menschen. Death and immortality in post- and trans-humanism. Transit – Europäische Revue 33 (2007), n.p. http://www.eurozine.com/die-vervollkommnung-des-menschen/, access: September 11, 2018, 2.30pm.

Lauth, Bernhard, Descartes im Rückspiegel. Der Leib-Seele-Dualismus und das naturwissenschaftliche Weltbild (Paderborn: Mentis, 2006).

McLuhan, Marshall, Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man (New York a.o.: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

Noble, Kathy, The Alternating Realities of Lynn Hershman Leeson. Mousse 47 (February-March 2017), pp. 152–165.

Pöhlmann, Egert, Der Mensch – das Mängelwesen? Zum Nachwirken antiker Anthropologie bei Arnold Gehlen. Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 52, no. 2 (December 1970), pp. 297–312.

Quick, Genevieve, Reflections in a Cyborg: Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Civic Radar. Art Practical (April 20, 2017), http://www.artpractical.com/column/feature-reflections-in-a-cyborg-lynn-hershman-leesons-civic-radar/, access: October 12, 2018, 10:15am.

Rae, Gavin, The Philosophical Roots of Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Imagery: Descartes and Heidegger Through Latour, Derrida, and Agamben. Human Studies 37, no. 4 (2014), pp. 505528.

Saage, Richard, Zur Aktualität der Philosophischen Anthropologie. Zeitschrift für Politik 55, no. 2 (June 2008): 123–146.

Spreen, Dierk, Was ver-spricht der Cyborg. Ästhetik & Kommunikation 26 (March 1997), pp. 86–94.

Tromble, Meredith, The Art and Films of Lynn Hershman Leeson: Secret Agents, Private I (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

Weibel, Peter, ed., Lynn Hershman Leeson. Civic Radar (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2016).

Weißmann, Karlheinz, Gehlen und Habermas. Sezession 29 (April 2009), pp. 20–23

Stefanie Wenner, Unversehrter Leib im ‘Reich der Zwecke’: Zur Genealogie des Cyborgs, in: Grenzverläufe der Körper als Schnittstelle, ed. Annette Barkhaus (München: Fink, 2002), pp. 83–100.

List of figures

Fig. 1: Zipping in Cyborg, 1963

Fig. 2: Inside Looking Out, 1967

Fig. 3: Dress Ray, 1966

Fig. 4: Woman with Fleeting Heart, 1964

Fig. 5: Dress Me 1, 2, 3 (3 plates), 1965

Fig. 6: X-Ray Woman, 1966

Fig. 7: Mirror Face Woman, 1966

For all: © Lynn Hershman Leeson

Courtesy of the artist and Bridget Donahue, NYC

Footnotes

1 Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline, Cyborgs and Space. Astronautics (September 1960), pp. 26–27 and pp. 74–76, here p. 27

2 See Gary Lee Downey, Joseph Dumit, and Sarah Williams, Cyborg Anthropology. Cultural Anthropology 10, no. 2 (May 1995), pp. 264–269.

3 Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto. Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s, in: The Cybercultures Reader, ed. Barbara M. Kennedy and David Bell (New York and London 2000), pp. 291–324. First published in: Socialist Review 15, no. 2 (1985), pp. 65–107.

4 See Pontus Hulten, The Machine. As seen at the End of the Mechanical Age (Greenwich, Conn. 1968). Matthew Biro, The Dada Cyborg. Visions of the new Human in Weimar Berlin (Minneapolis 2009).

5 See Ruth Bleier, Science and Gender: A Critique of Biology and Its Theories on Women (New York 1984).

6 See Harold Bloom, On the Origin and Evolution of Human Culture. American Scientist 51, no. 1 (March 1963), pp. 32–47.

7 Exceptions are Robotic Horse Interior, 1971, and X-Ray Man, 1970.

8 See Quick, Reflections in a Cyborg: Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Civic Radar. Art Practical (April 20, 2017), http://www.artpractical.com/column/feature-reflections-in-a-cyborg-lynn-hershman-leesons-civic-radar/, access: October 12, 2018, 10:15am. Alex Greenberger, A New Future from the Passed: Lynn Hershman Leeson Comes into Her Own After 50 Years of Prophetic Work. Artnews (March 28, 2017), http://www.artnews.com/2017/03/28/a-new-future-from-the-passed-lynn-hershman-leeson-comes-into-her-own-after-50-years-of-prophetic-work/, access: October 12, 2018, 10:15am.

9 Donna Haraway, Primate Visions. Race, Gender and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York 1989), p. 1.

10 See Jennifer John, Lynn Hershman ‚Roberta Breitmore’, http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/werke/roberta-breitmore/#reiter, access: October 9, 2018, 12.30am.

11 Oxford Reference, “BC,” http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095455853. Oxford Reference, “AD,” http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095349440, access: September 9, 2018, 1.30pm.

12 See Andreas Beitin, Face, Surface, Interface: The Motif of the Mask in the Work of Lynn Hershman Leeson, in: Lynn Hershman Leeson. Civic Radar, ed. Peter Weibel (Ostfildern 2016), pp. 198–209.

13 See Kathy Noble, The Alternating Realities of Lynn Hershman Leeson. Mousse 47 (February-March 2017), pp. 152–165, here p. 154. Noble describes the visitor as frightened, suspecting a corpse himself, while Beitin notes the visitor was drunk and called the police who then suspected a crime, see Beitin, Face, Surface, Interface, p. 203.

14 Some of the first exhibitions Lynn Hershman Leeson was included in were dedicated to the medium of the drawing: Adventure of a Line: Drawing Experiences by Lynn Lester Hershman, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, USA, 1966; Drawings U.S.A., Fourth Biennial, St. Paul Art Center, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA, 1969. See Weibel, Civic Radar, p. 373, p. 375.

15 See Beitin, Face, Surface, Interface, pp. 208f.

16 Beitin, Face, Surface, Interface, p. 207.

17 Cit. after Beitin, Face, Surface, Interface, p. 199.

18 Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man (New York a.o. 1964), p. 7.

19 Ernst Kapp, Grundlinien einer Philosophie der Technik. Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Kultur aus neuen Gesichtspunkten (Braunschweig 1877), p. 40, via https://archive.org/details/grundlinieneine00kappgoog, access: October 12, 2018, 10.30am.

20 Kapp, Grundlinien, p. 29.

21 Kapp, Grundlinien, p. 30.

22 Clynes, Kline, Cybernetic Organism, pp. 74–76.

23 See Arnold Gehlen, Die Seele im technischen Zeitalter. Sozialpsychologische Probleme in der industriellen Gesellschaft (Frankfurt am Main 2007), p. 6.

24 See Arnold Gehlen, Urmensch und Spätkultur. Philosophische Ergebnisse und Aussagen (Bonn 1956), p. 24.

25 See Egert Pöhlmann, Der Mensch – das Mängelwesen? Zum Nachwirken antiker Anthropologie bei Arnold Gehlen. Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 52, no. 2 (December 1970), pp. 297–312, here p. 298.

26 See Karlheinz Weißmann, Gehlen und Habermas. Sezession 29 (April 2009), pp. 20–23. And: Richard Saage, Zur Aktualität der Philosophischen Anthropologie. Zeitschrift für Politik 55, no. 2 (June 2008), pp. 123–146, here p. 125.

27 Haraway, Cyborg Manifesto, p. 313.

28 Kerry Doran, Cyborg Origins: Lynn Hershman Leeson at Bridget Donahue. Rhizome (March 19, 2015) http://rhizome.org/editorial/2015/mar/19/lynn-hershman-leeson-origins-species/, access: September 30, 2018, 4.30pm.

29 See Stefanie Wenner, Unversehrter Leib im ‘Reich der Zwecke’: Zur Genealogie des Cyborgs, in: Grenzverläufe der Körper als Schnittstelle, ed. Annette Barkhaus (München 2002), pp. 83-100, here p. 84.

30 See Dierk Spreen, Was ver-spricht der Cyborg. Ästhetik & Kommunikation 26 (March 1997), pp. 86–94.

31 See Oliver Krüger, Die Vervollkommnung des Menschen. Death and immortality in post- and trans-humanism. Transit – Europäische Revue 33 (2007): n.p., http://www.eurozine.com/die-vervollkommnung-des-menschen/, access: September 11, 2018, 2.30pm.

32 Fereidoun Esfandiary, Are you a transhuman?, cit. after Krüger, Vervollkommnung, n.p.

33 Krüger, Vervollkommnug, n.p.

34 Greenberger, A New Future.

35 Jean Baudrillard, Videowelt und fraktales Subjekt, in Aisthesis. Wahrnehmung heute oder Perspektiven einer anderen Ästhetik. Essays, ed. Karlheinz Barck (Leipzig 1990), pp. 252–264.

36 See Baudrillard Videowelt, p. 253.

37 See Bernhard Lauth, Descartes im Rückspiegel. Der Leib –Seele–Dualismus und das naturwissenschaftliche Weltbild (Paderborn 2006), pp. 56–58.

38 Quick, Reflections.

39 Gavin Rae, The Philosophical Roots of Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Imagery: Descartes and Heidegger Through Latour, Derrida, and Agamben. Human Studies 37, no. 4 (2014), pp. 505–528, here p. 507. Rae goes on to unravel the philosophical roots of Haraway’s thinking and relativises Heidegger’s influence by taking into account Agamben’s, Derrida’s, and Latour’s influence.

40 Rae, The Philosophical Roots, p. 525.

41 See Haraway, Cyborg Manifesto, p. 292.

42 Baudrillard, Videowelt, p. 260.

43 Baudrillard, Videowelt, p. 256.

44 Ibid.

45 Baudrillard, Videowelt, p. 263.

46 Charles Desmarais, Lynn Hershman Leeson: Myths and machines at YBCA. SFGate, (February 10, 2017), http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Lynn-Hershman-Leeson-Myths-and-machines-at-YBCA-10923873.php, access: October 12, 2018, 10.30am.

47 Clynes, Kline, Cybernetic Organism, p. 27.

48 See for example the work Dante Hotel in a Second Life, Life Squared, 2007.

49 Though Michel Foucault developed his ideas on the heterotopias before the internet was widely known, the internet might be seen as one of those spaces establishing own rules and reflecting society in a specific way. See Michel Foucault, Andere Räume, in: Aisthesis. Wahrnehmung heute oder Perspektiven einer anderen Ästhetik, ed. Karlheinz Barck (Leipzig 1992), pp. 34–46.

50 Beitin cites „McLuhan’s description of television in 1971 as a ‚totally new kind of mask,’ computer screens and tablet and smartphone displays have become the new, exponentially proliferating, and increasingly dislocated forms of the mask.“ Beitin, Face, Surface, Interface, p. 200.

51 Greenberger, A New Future.

LYNN HERSHMAN LEESON'S CYBORG DRAWINGS

Julia Heldt

Suggested citation: Heldt, Julia (2019). “Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Cyborg Drawings.” In: Interface Critique Journal 2. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang.

DOI: 10.11588/ic.2019.2.66987

This article is released under a

Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).

Julia Heldt is an art historian and works as a curatorial and scientific trainee at the Haus der Kunst in Munich.

“The subject in these drawings is not identifying itself via the mirror anymore, but has become one with the mirror, the screen, the interface, resulting in exposure and self-determination at once.”

INTRODUCTION: ZIPPING IN TO THE CYBORG

“made in U.S.A” is written in black, simple letters across the right side of the breast of a woman, drawn in pencil on a white piece of paper. (Un)zipping the vest with her left hand, a candid smile shows a row of small, regular teeth, and facing the viewer through her round glasses, the woman exposes her flat, white décolleté, (un)dressing herself. The vest itself displays a technical structure: lines resembling pipes or streets on a map are connected with a pump-like cylindrical construct, overlaid by a stomach-shaped organic structure in light pink. A heart in bright red, encircled by two bigger hearts, is linked with a pipe to the pump. The colour and structure of the forms are fading out towards the lower parts of the torso and the contouring lines of body and vest are blurred, loosened, blending into each other.

The double-sided work Inside Looking Out (fig. 2), from 1967 shows the front and back of a woman. Her body is not clearly outlined, though at some places yellow or green lines retrace the contours, still mostly bypassed by the translucent yellow fill colour. The back of her body is marked by her hair falling on her shoulders. Barely dressed, her roughly sketched hands, are held together over her bottom. Her skin colour is not even but shows in its present stage the age of the work itself. The rather simple back of her body is in no relation to what is pictured as her front. Without facial features, there are only abstract forms spread over her body which are stickers in the form of letters from an automated typesetting system. Hershman Leeson contrasts them with hand drawn parts, which can be found mostly on her lower torso, and includes technical drawings, such as fine arrows, dotted lines and cubes. Additionally, Hershman Leeson included heart shapes and drew simplified bones on her right upper leg. Having a phallic quality, the forms on her leg introduce a moment of sexuality to the drawing, further highlighted by a picture of an infant on her belly. The title of the work indicates that it is the inside of her body that we are looking at and that is looking at us. The drawing imagines the woman as a cyborg-like entity. The materialist approach to the female body opposes its essentialist truth as mother with a technologically altered anonymity. Inside Looking Out shows two ways of being a woman in a technological society, by appropriating it and by opposing it. Her crossed hands resemble a defensive motion, protecting her lower torso. Both parts of the work use their flatness: the first one creating a screen on which to present its interior to the exterior, the second one shutting itself out from any exterior, refusing communication.

Fig. 1: Zipping in Cyborg, 1963

The drawing Zipping in Cyborg (fig. 1), made by American artist Lynn Hershman Leeson (*1941, Cleveland, Ohio) in 1963 in pencil, watercolour and ink on paper, constitutes an early image of a then newly coined term: The Cyborg. It was introduced by scientist Manfred Clynes and physician Nathan Kline in the short text titled “Cyborgs and Space”, published in the September issue of Astronautics in 1960. Clynes and Kline propose the concept of the cyborg as an acronym for cybernetic organism, which is supposed to describe a “self-regulating man-machine system.”1 This system should serve as an augmentation of the human body making it able to survive in hostile environments during space travel. Growing out of the first years of the Cold War, the cyborg became a prominent figure connected with socio-cultural implications, redefining the being of humans in a world of new technology.2

One of the most famous interrogations of the cyborg term in relation to cultural and social paradigms is probably Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” from 1985.3 Haraway used the figure of the cyborg strictly metaphorically: To her, its image was a way to describe a cultural and social shift away from binary paradigms, emphasising its metaphorical quality, rather than its application in science. Before Haraway used the cyborg image for her feminist social theories and even before Clynes and Kline introduced the acronym, artists had been working with the concept of the human-machine fusion for a long time, for example Leonardo’s well known Vetruvian Man (1490), but especially since the beginning of the 20th century, when a growing involvement can be observed, with Dadaism and Futurism.4 Both Avant-garde groups subvert in their artworks the sovereignty and uniqueness of the human, by picturing their utopist visions of man-machine-fusions, blurring the boundary between human and technology, dismissing the sovereignty of the human and, at the same time, completing it with machines, referencing the century old reading of the human, and, especially, the woman, as inadequate and incomplete.5 Defining the production and use of tools as one of the earliest characteristics or skills of humans and their culture,6 the history of prostheses finds its technological equivalent in the cyborg, completing, augmenting or extending the human body and mind. Being situated on the unclear borders of human and technology, the cyborg works as an interface, through which the human can operate the technological – or through which the human can be technologically operated.

The focus of this essay is to look into the imagery of the cyborg that was produced around the time of the birth of the cyborg term. In a series of drawings, Lynn Hershman Leeson depicted mostly women7 in the tradition of human-machine fusions – especially Hannah Höch and Eva Hesse come to mind – and illustrates with these drawings social and cultural qualities of the cyborg. The female body, which is in those early drawings of Lynn Hershman Leeson often enough herself,8 is becoming an interface, being a surface of intersection, communicating mind and exterior, showing the direct influence of a societal shift and the way the female subject responds to this – be it with appropriation or shutting down. The flatness of the paper underlines the body as surface and becomes a kind of interface itself, a screen on which Hershman Leeson projects herself and her ideas. The cyborg, “born on the interface of automaton and autonomy”,9 is in these drawings too an interface between human and machine, aligning with Haraway’s theory through showing the possibility to dissolve boundaries and power structures and eventually creating a new way of thinking about the conception of the subject, that is mostly the female subject, in an evolving technological and digital world.

DRAWINGS ON SCREENS

Lynn Hershman Leeson divides her almost six decades spanning œuvre in two elementary stages: Before Computers (B.C.) and After Digital (A.D.). 10 She appropriates the terms that are being used to label years in the Julian and Gregorian calendars, indicating the years before Christ (BC) was born and after His Birth, anno domini (AD).11 By doing this, she puts not only the invention of the computer in direct relation to the birth of Christ, indicating that both are highly effective shifts in human history; but she also establishes a new history writing – one that is based on technological evolution, which shows a techno-centric worldview superseding the Christian worldview.

Hershman Leeson became known to be a vanguard artist in the use of technological and digital evolution in her works, though one of her most known works, the early performance The Dante Hotel (1973-1974), featuring two “life-size dolls with wax-heads”, which she modelled after her own face, placed in a hotel room, used technology only in a hidden way. The dolls, who made breathing sounds and moved slightly occasionally, are part of her Breathing Machines, a series of masks, she started making in 1965.12 Humanising these sculptural works by making them breathe and putting them in the hotel room, resembling real guests, Hershman Leeson blurs the boundaries between human and machine, fiction and reality – the installation was eventually shut down after a visitor called the police who suspected a crime scene at the hotel room.13

Around the same time as she began working on her Breathing Machines, Hershman Leeson addressed this topic in a series of drawings, which will be at the centre of the following essay. These drawings can be seen as the groundwork for her art, not only being the first she made that gained attention,14 but mostly because they are building the basis for her interrogation of the technological influence on the individual and society, as she came back to the image of the cyborg throughout her career, for example in works like the Phantom Limb Series (1985–ongoing), Seduction of a Cyborg (1994), Cyborg Series (1994–2006), Teknolust (2002), and others. She too continued to create works of art, which display a more distinct understanding and literal use of reciprocal interfaces, most prominently Lorna and Deep Contact (both 1984).15 In these early drawings, as I will show, a first understanding of the relation of women and technology is taking shape, establishing an abstract thinking of interfaces, less focused on user-device reciprocity and more on the literal meaning of interfaces as surfaces of intersection. Within those early works, she introduces an aesthetic that is both mechanics and technology related, but at the same time features forms and subjects that are highly idiosyncratic. The drawings are not accurate depictions of structures but speak of emotions and figuring out.

The double-sided work Inside Looking Out (fig. 2), from 1967 shows the front and back of a woman. Her body is not clearly outlined, though at some places yellow or green lines retrace the contours, still mostly bypassed by the translucent yellow fill colour. The back of her body is marked by her hair falling on her shoulders. Barely dressed, her roughly sketched hands, are held together over her bottom. Her skin colour is not even but shows in its present stage the age of the work itself. The rather simple back of her body is in no relation to what is pictured as her front. Without facial features, there are only abstract forms spread over her body which are stickers in the form of letters from an automated typesetting system. Hershman Leeson contrasts them with hand drawn parts, which can be found mostly on her lower torso, and includes technical drawings, such as fine arrows, dotted lines and cubes. Additionally, Hershman Leeson included heart shapes and drew simplified bones on her right upper leg. Having a phallic quality, the forms on her leg introduce a moment of sexuality to the drawing, further highlighted by a picture of an infant on her belly. The title of the work indicates that it is the inside of her body that we are looking at and that is looking at us. The drawing imagines the woman as a cyborg-like entity. The materialist approach to the female body opposes its essentialist truth as mother with a technologically altered anonymity. Inside Looking Out shows two ways of being a woman in a technological society, by appropriating it and by opposing it. Her crossed hands resemble a defensive motion, protecting her lower torso. Both parts of the work use their flatness: the first one creating a screen on which to present its interior to the exterior, the second one shutting itself out from any exterior, refusing communication.

Fig. 2: Inside Looking Out, 1967

The blending of surface and interior, or putting the interior on the bodily surface is characteristic for Hershman Leeson’s early drawings, as can be seen in Dress Ray (1966, fig. 3), too. Using again collage techniques and drawing, Hershman Leeson here opens the flat space of the drawing and indicates spatial qualities, through the figure’s head turn to her right, while its title alludes to x-ray technology. Utilising the concept of the bodily surface, the skin and clothes, to examine the construction of the subject, she deploys historically and socially established features of women, but shifts their perception: The purple dress as feminine object becomes an x-ray screen or interface, being distinct from the white skinned female body. The dress like the skin, in Inside Looking Out, function as screens, representing an imagined biological and technical interior of the body, interspersed with emotional features with images of hearts and infants. In both works, the internal subject and the external technological society are intertwined in the cyborg figures.

Fig. 3: Dress Ray, 1966

As with her Breathing Machines, Hershman Leeson makes use of the cultural topos of hiding or creating an identity, as Andreas Beitin notices:

„Beyond its sociocultural frame of reference, the mask as a second or alternative face can be inscribed in a terminological, etymological, epistemological, and not least technological line of development: face-mask-surface-interface-screen. Computer screens and tablet and smartphone displays, as today’s masks, offer an unlimited supply of electronic changes of identity.”16

And Hershman Leeson herself notes, that “Today, masks are interfaces that mutate through connectivity, merging the past and present through use.”17 Though Beitin focuses on newer works in his reading, creating an evolution in the use of masks, my point here is that the early works too show a conceptual understanding of interfaces as masks. By examining bodily surfaces, Hershman Leeson approaches the materialist notion of identity in relation to a technocratic society. This reading of the cyborg drawings as masked, questions the understanding of them as a projection of the interior, that I will discuss further along, or a looking in to the interior and rather proposes of them to be read as a way of superficial adaption to a new technological society. That the human has always been in need of adaption to its exterior and the materialist understanding of the cyborg as alteration and augmentation of the organism that is the human body will be the focus of the following chapter, taking into consideration the social and individual implications, especially on women, which this materialist reading of the cyborg can have.

THE INSUFFICIENT HUMAN

When in 1964, Herbert Marshall McLuhan wrote his iconic words, “the medium is the message”, he substituted them with the limitation that “[t]his is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium – that is, of any extension of ourselves – result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.”18 McLuhan, by introducing the reflexivity of technology and media into the social and personal conditions of humans, defines the media in the quoted insertion as an “extension of ourselves.”

The image of media as an extension of the human, or as McLuhan writes in the subtitle of the same book, “The Extensions of Man”, is based on an anthropocentric world view. Aligned with this, Ernst Kapp in his “Grundlinien einer Philosophie der Technik” (1877) traced the reading of tools as an extension of the body, based on the etymology of the Greek word organon, which means limb, its afterimage, the tool and even the material of which the tool is made.19 Kapp describes the history of civilisation as a history of labour and thereby drafts a materialist reading of society, describing human nature as one which always first creates his/her own culture. Unlike animals who survive because of their instincts, humans are, according to Kapp, in need of science and artificial creation.20 He goes on to describe the term “Projection”, which is in itself a mode of extension. Kapp uses the term Projection to explain the relations of emotions towards exterior things and the creation of imaginations.21 This metaphorical or imaginative reading of Projection adds a theoretical understanding of the extension of the human to the physical one, which tools stand for. Kapp’s imaginative and materialist extension of the human body and mind finds its equivalent in the reading of the cyborg figure, that I am discussing here. Augmenting the human body and mind, as Clynes and Kline imagined,22 the cyborg functions as the postmodernist tool extending the subject. Though the term Projection signals a one-way mode of communication, it functions as an interface too. That the cyborgised interfaces in Hershman Leeson’s drawings function as masks, a way not only to adapt to the exterior by superficially reflecting it, but also as possibly hiding the interior, or, at least communicating a mediated, altered or limited persona through it, relates to Kapp’s idea of Projection.

Another example for this is Woman with Fleeting Heart (1964, fig. 4), depicting a woman’s head to which a heart shaped structure is attached by a chord, being prostheses and projection at the same time, the heart appears outsourced of the woman’s body, her glance absent and behind her a shadow that is more of a doubling. The shadow might in this case indicate a narrative time, a before and after, dissolving the flatness of the paper screen or another kind of simplifying mask, layered before her own more profoundly sketched face. In this case, the cord connecting heart and woman signifies the interface, a string of intersection rather than a surface. That the heart in contrast to the woman’s body, at least what we see of it, is highly marked by technological drawings, more detailed than the contours of the woman herself, and her melancholic almost empty gaze, implies a technological augmentation of an insufficient woman, who became incomplete through almost losing her heart.

Fig. 4: Woman with Fleeting Heart, 1964

This notion of incompleteness, physiologically or socially, is also found in the techno-philosophical concept of Kapp and his followers. It is not just that humans need augmentation to survive in space, like the cyborg figure, but according to some conservative cultural anthropologists they also need it to survive in general. The human need for augmentation is exemplified by Arnold Gehlen’s term of the “Mängelwesen”, a deficient being, which he coined in his 1940 published work “Der Mensch: Seine Natur und seine Stellung in der Welt”. Gehlen advocates the importance of tools, as they are the defining element of humanity: Only where there were tools in history, there were beings defined as human. The need for these tools is explained by Gehlen through the incompleteness of the human body. Lacking certain organs and instincts, the human could not have survived without creating tools and augmenting his surroundings intelligently.23 Like Kapp, who also describes humanity’s history as a history of tools, Gehlen describes tools and their subsequent technology, as prostheses for humans. He uses the term Mängelwesen as an immutability of the conditio humana, demanding the human trait to learn, to adapt to new situations to be stabilised,24 which can be achieved through use of technology. That Gehlen’s reading of the human as Mängelwesen – a term originally introduced by Johann Gottfried Herder25 – and his subsequent demand for strong institutions, meaning regulatory systems should be seen critically is underlined by his historical background as a member of the NSDAP and his conservative “Philosophy of Institutions” from the after-war years, which found a strong opponent in the Frankfurt School, namely the critical theory of Jürgen Habermas.26 Though the cyborg figure as such evidently functions as just what Gehlen demanded – a tool to augment the human body and mind – it’s cultural appropriation of the after war years, most prominently Donna Haraway’s metaphorical use of it but also Hershman Leeson’s more literal use, oppose Gehlen’s techno-philosophical approach, by underlining the individualistic quality of the cyborg image. This is especially evident in their use of female cyborg images and their possibility to (de)construct their selves.

THE CYBORG AS COMPLETION OF THE INSUFFICIENT WOMAN

While Clynes and Kline had a specific idea of the cyborg in mind, a control system that can be used for those travelling to space, the cyborg concept that is advocated by Lynn Hershman Leeson and Donna Haraway, demands a structural understanding. Haraway’s cyborg concept disrupts established power structures and institutions, as she summarises towards the end of her Manifesto:

“To recapitulate, certain dualisms have all been systemic to the logics and practices of domination of women, people of color, nature, workers, animals – in short, domination of all constituted as others, whose task is to mirror the self.”27

Dissolving those dualisms, the cyborg figure questions power relations those dualisms and social institutions have established.

While Haraway’s cyborg remains completely metaphorical, Hershman Leeson deploys a subversion of power structures in her cyborg drawings, that is of a more literal quality. In the three-part work Dress Me (fig. 5), from 1965, she shows a woman in three stages. In the first, the woman’s body remains plain, outlined only by black pencil strokes. Bold letters read “DRESS ME” across her chest. Gazing to her left, she seems to be expecting someone following her invitation, resembling paper dolls, that children can dress in various outfits. The second part of the work consists of a bright red drawing of a dress, ready to be laid over the woman-figure.

Fig. 5: Dress Me 1, 2, 3 (3 plates), 1965

The third part shows the interior of the woman, similar to the other works already discussed and X-Ray Woman (fig. 6), mechanical drawings and figures cover an area in the shape of a torso, missing limbs. As Kerry Doran writes, the two outfits are options that determine the woman’s self – at least for that day –:

“She longingly looks toward her two garment options: an average looking coral frock or a diagram of parts, words, and pieces, appearing simultaneously deconstructed and reassembled, as though taking in the outside forces that seek to define a woman wearing a dress in the world […].”28

Fig. 6: X-Ray Woman, 1966

Simultaneously depicting the woman as a doll, who is subjected by the ones who dress her and as an individual that can create her own reality by her choice of clothes, Hershman Leeson’s woman in this drawing is still an insufficient self, “longing” for augmentation, be it through clothes that make her herself or an outside power that imposes their opinions on her, thereby situating the woman in the context of an evolution of independence of the years the work was made.

The concept of the Mängelwesen can be seen as a predecessor-figure for what came to be the cyborgised human.29 As humans needed tools to establish their culture and ensure their survival, they took on to need technology to do the same, which resulted in the technologically augmented human. Completed and improved not just by technological tools like cell phones and the computer but also by medical tools, which establish the human beyond its natural transiency.30 This emancipatory quality of the cyborgised human towards nature, is the core figure of the post- and trans-humanist theories, and it comprises the image of a New Human, in which human and machine create the interface that is the augmented human body.31 This yields into a freeing state for the human, who is not subjected by nature anymore, as trans-humanist Fereidoun M. Esfandiary writes: “So as long as there is death no one is free.”32 As transhumanism wishes the human to not just become one with machines, but outsource mind and memory into computers, to abolish death and be able to live forever within the cyberspace,33 the cyborg figures of the 1960s are early positivist images of the wish to overcome natural and social preconditions and establish a self-determined life and self. Hershman Leeson’s images speak of these ideas and narrow them down to the position of women in 1960s USA. Her feminist approach to undermine essentialist notions of what it is to be woman was continued by Haraway, as she too uses the human-machine fusion to dismantle human and female preconditions, social as well as natural. In contrast to this, Gehlen does not describe the possibility of technology to liberate humanity from its natural burdens, but rather sees it in its culture creating way, to establish rules and paradigms in the form of strong institutions, rather than to overcome them.

The cyborg was intended to augment the human. Hershman Leeson uses the cyborg image in her works to question the very being of the Human, or in most cases, women in the form of “feminine machines.”34 She thereby inverses the implication of power structures that Gehlen sees in technology and dissolves them, by dissolving the constitution of the female body, opening it up to interrogation via x-ray and including the mechanical into its essentialist nature. The depicted women openly wear their relation to the exterior in their bodies, becoming themselves interfaces. In the case of Dress Me, the human body as interface, stands for the possibility to self-government and emancipation. This positivist reading, though, needs to be seen ambivalently: Women emancipating themselves were just recently oppressed women; their empty faces and eyes or the isolation of the backside of Inside Looking Out, for example, speak of this ambivalence towards the technological influence on the individual.

THE CYBORG AS EXTENSION OF THE MIND

A similar conservative or pessimist point of view as Gehlen’s is represented by Jean Baudrillard in a lecture held at the 1988 conference “Philosophie der neuen Technologie” in Linz, Austria. Baudrillard claims in his subsequent essay “Videowelt und fraktales Subjekt” that the human is only living as a “fractal subject”, a subject broken into pieces, more and more abandoning its social skills and only differing from machines in its ability to feel “passion”.35 According to Baudrillard, the human as a subject becomes increasingly insensitive and is only able to live and feel because of technological prostheses.

Following McLuhan’s theory of the extension of the human through technology, Baudrillard describes the brain in separation of the body, the body as an excess of the mind.36 Baudrillard adapts the Cartesian theorem of the mind-body-dualism, in which Descartes describes the human as a machine as well,37 and transcribes it to the postmodern age. In his idea of the “fractal subject”, the mind is split into parts, an idea that can be seen in relation to the cyborg, in which single body parts are individualised and outsourced or replaced, as they become subject of augmentation in Clynes and Kline’s proposal, or in Hershman Leeson’s view, splitting up the body in flattened front and back and screening its interior with mind and heart being external. The material body becomes the interface, communicating between mind and society, thereby detaching itself from the first. The divisibility of the human body in view of technology is present in another series of works by Hershman Leeson titled Phantom Limbs (1985–1987), that consists of photographs of women whose body parts, such as their heads, legs or arms are replaced by cameras, screens or sockets and that Genevieve Quick described as “spectral bod[ies].”38

Like Baudrillard, Haraway takes part in the question of mind-body-separation, as Gavin Rae suggests that her “thinking is profoundly, if implicitly, influenced by Heidegger’s critique of the binary oppositions underpinning Cartesian anthropocentrism.”39 Rae summarises Haraway’s endeavour with her questioning of “what it is to be ‘human’”40. Opposing feminist essentialism, she uses the cyborg imagery to dissolve body-mind boundaries as well as many other dichotomies.41 Her positivistic approach contrasts with Baudrillard, who considers the dissolving of the human entity through technology a loss of sociality, of empathy towards the self and others. Baudrillard goes on to disagree with McLuhan, who too sees the extension of the human through technology as potential and claims that the parts of the human body, including the brain, have separated themselves from the human and surrounding it “eccentrically” instead of “concentrically”. The parts of the body, that Baudrillard thinks of as prostheses, are highly influenced by the technology surrounding them, even becoming one with it, viewing human and machine as inseparable.42

Baudrillard’s negative evaluation is mostly based on the shift he sees in the self-identification of the subject and the bodily screen as interface, claiming, that the “video stage has superseded the mirror stage.”43 The subject only views and communicates itself via the mediated medium of the screen dominated by superficiality and meaninglessness, instead of the immediacy of the mirror. According to Baudrillard, the screen cannot be used for an active analysis of one’s own, but only as a self-monitoring tool in an “instantaneous and superficial refraction”.44 The “refraction” of the self-image describes a shifted view of one’s self, caused by the medium. Baudrillard states that

“we once used to live in the imaginary of the mirror, the divisiveness and the I-scene, the alterity and the alienation. Today we are living in the imaginary of the screen, the interface and the multiplicity, communication and network.”45

The subject, in Baudrillard’s pessimist understanding of technology, is dominated by the perception through screens and interfaces, without being able to differentiate between singular identities, the subject is only one part of a bigger picture. The identification of the self, that Baudrillard seems to be missing in the “videoworld”, is of similar complications as the identification of Hershman Leeson’s cyborg drawings, as they too perceive and project only a mediated version of themselves through their bodily screens.

The identification of one’s self through the view of others is what Hershman Leeson addresses in her drawing Mirror Face Woman (1966, fig. 7) too, as Charles Desmarais describes the depicted woman as someone, “who exists as a reflection of others who is alive only on the viewer’s terms.”46 Hershman Leeson’s mirror-faced figure is like those other early drawings marked by technical details. Her broad shoulders and straight uplifted left arm indicate strength that contrasts the interpretation of her mirrored face by Desmarais. Subverting the negative interpretation of the superficiality of her mirrored face, it can too function as a shield. Mirroring the exterior, shielding her mind of it, Mirror Face Woman exists on the verge of being independent and defined by others, at the same time declining a communication, throwing the perceiver back at herself, becoming an interface in the meaning of a mask only in a one-way direction.

Fig. 7: Mirror Face Woman, 1966

CONCLUSION