AMERICAN PSYCHO. READING AN ALGORITHM IN REVERSE

Karl Wolfgang Flender

“Google recommends a pulse monitor while someone’s bleeding to death, or suggests skin tightening while Bateman makes sausage of a victim.”

INTRODUCTION

“UNSER SCHREIBZEUG ARBEITET MIT AN UNSEREN GEDANKEN”, Friedrich Nietzsche famously remarks on his use of the Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, a forerunner of the typewriter which was developed for the visually impaired.1 Originally acquired by the shortsighted philosopher because of his rather illegible handwriting, the machine began to slowly affect his writing and thinking. Alluding to Nietzsche’s new telegram style and the capital letters (the Writing Ball did not have miniscules), his assistant, Peter Gast alias Heinrich Köselitz, observes in a letter: “Sowohl von der Deutlichkeit der Lettern, noch mehr aber von der Kernigkeit der Sprüche war ich überrascht. […] Vielleicht gewöhnen Sie Sich mit diesem Instrument gar eine neue Ausdrucksweise an.”2

Examples in literary history are legion, that each writing tool yields new materialities of text, new forms of writing and ways of thinking: The pencil for example allowed Goethe to effortlessly jot down his nighttime-inspirations, while Georg Lichtenberg’s experimental use of the quill resulted in his famous Sudelbücher (if need be, the quill dipped into coffee instead of ink); Kerouac binge-wrote On the Road on his Underwood Portable, the typewriter also enabling the typographic experiments of the Concrete Poets – in poetological texts and literary experiments writers investigate their respective writing tools as the technical conditions of the possibility of literature.3

With the advent of the personal computer, digital writing tools and their increased enmeshment through cloud-services, we have entered a new epoch of writing, in which “the interfaces themselves and therefore their constraints are becoming ever more difficult to perceive”, as Lori Emerson has noted in Reading Writing Interfaces.4 She has shown how the complex workings of digital writing tools under their shiny graphical user interfaces (GUIs) have become less and less observable to users, let alone comprehensible, since input and output are seemingly disconnected through opaque algorithmical operations and paradigms of user-friendliness and intuitive design, while the possibility of user’s choice has been strategically limited by software companies.5 The everyday digital writing tools thus appear as closed-off black boxes to the users,6 ever increasing the writer’s dependence on the Eigensinn of his or her tools.7 Or, more drastically put, as Emerson concludes at one point: “[T]hey frame what can and cannot be said.”8

Just think of the automatic spellchecking in Microsoft Word, which does not disclose on grounds of which grammatical rules or dictionary this or that word is underlined; or the AutoCorrect-function of Apple, which almost unnoticeably capitalizes words or corrects mistakes, whether or not the user intended it. AutoComplete interferes with smartphone-messaging, when words are proposed on grounds of a statistical or stochastic body that has been trained on the user’s habits; search engines complete search terms to entire sentences, and therefore influence what is searched and thus found; not to mention the most complex language technologies such as Google Translate and its machine learning algorithms.9

While one can get quite weary of reiterating how writing today is subject to international surveillance and corporate control – and that conditions of literary production, distribution and reception are becoming ever more intertwined with commercial, political and power interests as these writing tools have become the widely accepted and unchallenged norm –, a range of contemporary literary experiments still serves as a fresh take to critically assess these tools.

Suggested citation: Flender, Karl Wolfgang (2019). “American Psycho. Reading an Algorithm in Reverse.” In: Interface Critique Journal 2. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang.

DOI: 10.11588/ic.2019.2.66992

This article is released under a

Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).

Karl Wolfgang Flender is a Ph.D. student at the Friedrich Schlegel Graduate School for Literary Studies at Freie Universität Berlin, investigating the interrelation of technology and knowledge in contemporary, experimental book-based literature. Having studied Creative Writing at the University of Hildesheim, he has published two novels with DuMont publishing house, Greenwash, Inc. (2015) and Helden der Nacht (2018). In 2019/2020 he will be Visiting Scholar at Columbia University.

Selected Publications:

Karl Wolfgang Flender, Literary forkbombs. Interventionist Conceptual Writing in the Age of Amazon. In: Hyperrhiz. New Media Cultures 20, (2019). doi:10.20415/hyp/020.net01

Karl Wolfgang Flender, #nofilter. Self-narration, identity construction and metastorytelling in Snapchat, in: Interface Critique, ed. Florian Hadler and Joachim Haupt (Berlin 2016), pp. 163–179.

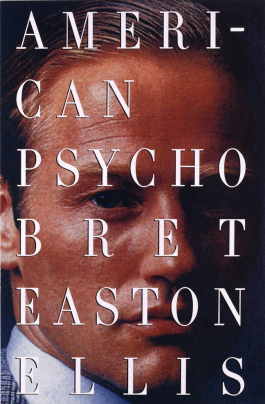

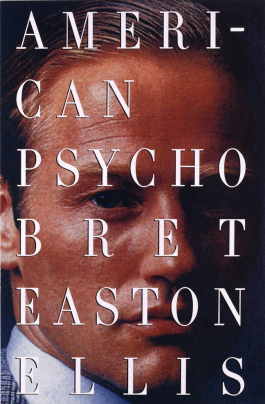

Fig. 1: Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho, Cover.

Fig. 2: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho, Cover.

AMERICAN PSYCHO (2012): BLACK-BOX-TESTING OF AN ALGORITHM

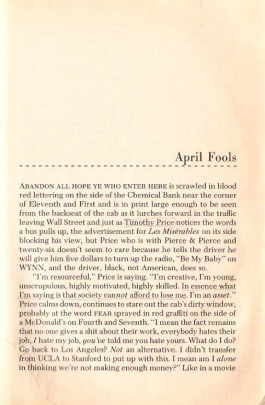

“ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE”,10 are the first, Dante-channelling, words of Bret Easton Ellis’ infamous novel American Psycho, published by Vintage Books in 1991, in which the brand-obsessed investment banker and yuppie Patrick Bateman turns into a perverse mass murderer. The eponymous 2012 edition of the book however, released by the publishing collective Traumawien, and, judging by its cover, also written by Ellis, begins like this:

“Crest(r) Whitestrips Coupon, Save $10 Now on Crest(r) Whitestrips. Get Whiter Teeth for the Holidays! Coupons.3DWhite.com/Whitestrips!”11

At first glance, one merely seems to be holding a cheap bootleg, at some stage of the illegal copying process infested by advertisements, a spambook so to say: Jacket, half-title and typesetting imitate the original’s design and typography, the chapter titles are identical, yet the 408 pages of the 2012 edition are almost completely white, except for constellations of footnotes, in which said advertisements appear (see fig. 1–4). On closer examination however, American Psycho (2012) turns out to be the result of the creative (mis-)use of a contemporary writing technology, namely Google Mail, as if taking to heart that “[t]he only conceivable way of unveiling a black box, is to play with it.”12

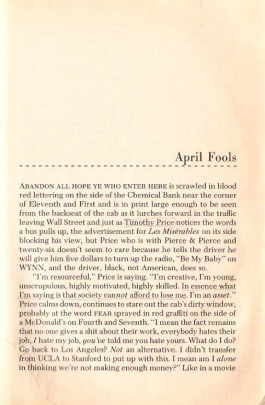

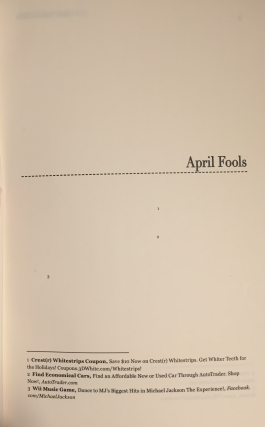

Fig. 3: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho, p. 3.

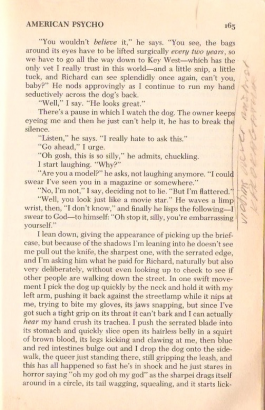

Fig. 4: Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho, p. 3.

For their American Psycho, the artist duo Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff sent Ellis’ novel page by page between to Gmail-accounts to and fro, and saved the ad-banners which appeared in the graphical user interface of the mail program. These so-called “relational ads” are generated through algorithmic keyword analysis of the email’s text, as when signing up for Gmail one automatically agrees that all in- and outgoing mails will be analysed to serve personalized ads (“we are always looking for more ways to deliver you the most useful and relevant ads”, it says on Google’s support-page). Subsequently, Cabell and Huff annotated the novel page by page with the collected ads, placing footnotes behind each word that presumably triggered the respective ad – for example, an ad for the already mentioned “Whitestrips Coupons” would be placed behind “teeth”. Then Cabell and Huff erased the original text of the novel, leaving us with blank pages and constellations of footnotes.

To read American Psycho (2012), one can thus consult a copy of the original to compare pages (see fig. 3 and 4), or download the freely available PDF-version, in which the original text is not deleted but only “whitened out” and can easily be rendered visible – the authors clearly encouraging such a reading.13 One then encounters multiple processes of reading and writing constellated in American Psycho (2012) for the reader to decipher: Google’s algorithm has “read” – aka processed – the pretext page by page (input) and written the ads (output), Cabell and Huff have compared the output to the pretext and positioned the ads in footnotes: In a black-box-testing-spirit feeding a canonical novel into the writing technology Gmail, Cabell and Huff render visible the opaque workings of the algorithm in the discrepancy between pretext and new text.

The same page of American Psycho (2012) in various mediations: (1) in print

(2) as pdf

(3) as pdf, with the text marked through the command select all

As one starts to follow the algorithm through the book(s), one basically tries to get into the algorithm’s head: Why does this or that ad appear on this particular page? Where is the keyword that triggered it? Is there one – or is the output not only influenced by the text on the page, but by some other signals like IP-address or previous searches…?14 Furthermore, one starts to compare passages/keywords throughout the novel, which apparently triggered identical ads – the common denominator, at times impossible to find. This is only complicated by the fact that one already reads a human interpretation of the algorithm – Cabell and Huff placed the ads “by hand” –, so if ads seem to be arbitrarily attached to keywords the reader might start looking for more adequate keywords on the same page, or at times even presumes that strategic authorial intervention could be at play…15

Reading the new American Psycho in this manner, one thus reconstructs the authors’ process of composing the text, retraces the workings of Gmail’s algorithm, and at the same time reads a translation of a novel, famous for its portrayal of 1980s consumer culture, into a present whose consumer culture is dictated by online advertisement – all three ways of reading deeply intertwined with each other.

ALGORITHMIC ACTUALIZATION AND LITERACY IN LINGUISTIC CAPITALISM

Reading American Psycho (2012), it is astonishing how close to home the advertisements hit: If in the “original” there are page-long descriptions of Bateman’s frenemies’ suits, ads for clothes appear (“Dress Shirt – SALE $29.89 / 60% OFF Robert Talbott / Dress like a secret agent / Joseph Bank Mens Shirts / R Laurens: Secret Sale”);16 high-end audio equipment is praised when Bateman plays music; a two-pager about drinking water is accompanied by six ads for “LIFE Water Ionizers(tm)” or “Free Water Cooler Rental”,17 and last but not least, the notoriously recurring “Crest(r) Whitestrips Coupons” (on 81 out of 408 pages!), give away Bateman’s obsession for teeth (and/or Google’s fondness of bleaching-ads). Sometimes the algorithm even uncannily grasps the gist of a scene, for example when an “Instant Tenant Screening” and criminal checks are advertised, while Bateman is interrogated by a homicide detective.18

The conceptual match of pretext (a novel about consumer culture saturated with brands) and applied procedure (keyword-triggered algorithms to display ads), results in an awkwardly adequate actualization of American Psycho for the present, as of course all the products in the footnotes stem from the year 2012 and not from the 1980s. The absurdity of the breathless 2012 online-advertisement-sound seems at times to perfectly match the surface-fixated Bateman:

Luxurious Volume, Full Bodied Hair. Seriously High Style. A New Level Of Fullness, www. JohnFrieda.com / 479 Short Hair Pictures, Find inspiration for your next cut with our short hairstyle pictures., Short-Hairstyles.StyleBistro.com / Clip-On Hair Extensions / Face Tightening Secret / 60 years old … A must see. FlexEffect Facialbuilding / Get Soft, Natural Curls.19

As an effect of this actualization, interesting superpositions appear. While in the original Bateman programs his VHS-recorder to record The Patty Winters Show, in the new version mp3-players are offered – in general, so it seems, the most striking difference between 1991 and 2012 are not the advertised clothes, furniture or food, but the media change as it is heralded in this ad: “Tape To Digital Converter, Convert Any Cassette Tape To Digital MP3 In 3 Easy Steps! $59.95, www.CassetteToUSB.com.”20

Gmail’s ad-placement, as illustrated in American Psycho (2012), is an expression of what Frederic Kaplan calls “linguistic capitalism”, namely the current state of permanent algorithmic evaluation and commodification of linguistic material via language and writing technologies.21 With Google as example, Kaplan describes how the linguistic capital of accumulated search-entries is translated directly into revenue through algorithmic keyword-auctions: Each word or sentence that is entered into Google’s interface is auctioned in split seconds to advertisers, whose ads are then displayed in the results. Kaplan concludes: “Some words and expressions have therefore become commodities with different monetary values that can be ‘bought’ from Google. In some sense, Google has extended capitalism to language, transforming linguistic capital into money.”22

This is also the case with Gmail and American Psycho (2012): For each keyword that has triggered an ad, a price has been paid (which makes one wonder how much money Google earned from the 819 ads in the making of the book); each word has been awarded a price in the logic of “linguistic capitalism”: it is treated and calculated according to statistical bodies, regardless of its narrative or semantic context, clearly implying a different sort of reading and appreciation of text than we human readers are accustomed to.23 The configuration of both cultures of reading in one text highlights the threshold and/or transition from human to digital/machinic/algorithmic literacies – they “read” differently.

ALGORITHMIC MISMATCHING AND THE POLITICS OF THE ALGORITHM

Besides the succeeding actualizations, the most striking feature of the new American Psycho are the absurdities, inaccuracies and paradoxes that originate from the algorithmic mismatches of semantic content and respective ad. If there’s “salmon au lait” on a restaurant menu, Google proposes to “Learn French in 10 Days”;24 another time it is obviously misinterpreting “chow-chow” and offering “Cheap Cowhide”25 (which for the knowing reader almost seems like an uncanny premonition to the skinning of people which will occur later in the novel), or having – without apparent keyword – a PR-campaign from the present of 2012 intrude the equally catastrophy-ridden Eighties: “BP, Info about the Gulf of Mexico Spill Learn More about How BP is Helping., www.BP.com/ GulfOfMexicoResponse.”26

Fig 6: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho, p. 174.

Fig 7: Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho, p. 165.

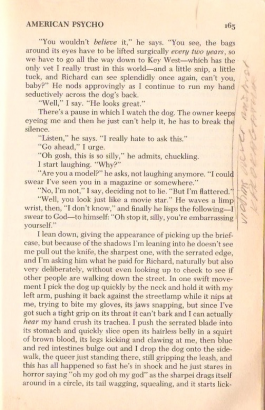

As one continues reading the novel(s) and Bateman begins his spree of murder and rape, the algorithm’s disturbing indifference towards violence becomes apparent: During the detailed description of the slashing of a dog, porcelain knives, knife sharpeners and a haircut are advertised: “[H]e doesn’t see me pull out the knife (Kyocera Knives on sale), the sharpest one (Best Knive Sharpener), with the serrated edge (Yoshi Blades Official Site)”. And a few sentences later: “I push the serrated blade into its stomach and quickly slice open its hairless belly (Great Haircuts).”28 – If Google’s goal is to provide users “with ads that are useful and relevant to their interests”,29 for a mass murderer like Patrick Bateman that apparently works just fine.

The list goes on and on: Google recommends a pulse monitor while someone’s bleeding to death, or suggests skin tightening while Bateman makes sausage of a victim. During these passages, which are unbearable to read and were responsible for American Psycho’s temporary indexing in countries such as Germany, the algorithm displays a decided insensitivity towards the semantic content and context. Googles full-mouthed ad policy can only be counted as a sarcastic comment to these observations: “[W]e are careful about the types of content we serve ads against. For example, Google may block certain ads from running next to an email about catastrophic news. In addition, we will not show ads based on sensitive information, such as race, religion, sexual orientation, health, or sensitive financial categories.”30

The reader’s amusement, ambiguity or disturbance regarding Gmail’s ad-placements, are again effects of the relationship of two different kinds of reading and their playing against each other in the book: the sense-making, semantic reading of human recipients and the algorithm’s keyword-oriented “reading”, or processing, of text against a database of ads.31 American Psycho (2012) is thus a hybrid book: Produced according to the logic of an algorithm32 but published as a printed book, the familiar narrative genre of the novel is what makes the taken for granted workings of the blackboxed writing interface observable through defamiliarisation: Gmail’s “ignorance” towards violence and racism and its willingness to serve ads on top appear as part of the bigger picture that similar technologies have been and are used in the “fight against terror”, equally combing mails for keywords, or how self-learning algorithms used in predictive policing exhibit racist attitudes with real-life effects, how hiring-tools of tech companies disadvantage women, etc.33 The programmed, economic, and political dispositif of the algorithm remains necessarily opaque, but here it can be glimpsed in the literary.

A POETICS OF THE GLITCH

As we have seen, not the perfect match of text and ad that facilitate this scrutinizing reading but rather the inconsistencies, paradoxes and mismatches throughout American Psycho invite the reader to reflect on the workings of the algorithm. Operationalizing the faultiness of an unperfected writing tool, Cabell and Huff employ a poetics of the glitch. Glitch theorist Rosa Menkman explains that a glitch appears when any medium is brought “into a critical state of hypertrophy” that allows to “subsequently criticize its inherent politics.”34 American Psycho (2012) does just that. It oversaturates a novel, which is already brimming with brand names, with even more advertising, bringing it into an unreadable “state of hypertrophy” and testing the sensitivity of a technology with page-long descriptions of slaughter. This critique in the guise of literature not only allows to reflect, but also to make tangible the politics of the program, as Nathan Jones notes: “[A] glitch is a moment which gives propulsion into an unforeseen area of critical enquiry – allowing us to not only observe, but experience beneath a media surface.”35

Admittedly, it is difficult to distinguish where the glitch begins and ends, as not only the artist or the faulty software are responsible for the glitch, but also the recipients who experience something as glitchy, as “glitches only exist against human expectations. […] [A] glitch comes into being solely at this moment of transversal entanglement between human and technological systems.”36 That said, the hypertrophy and seeming immorality of Gmail’s algorithm as displayed in American Psycho may also merely be effects of a human reader’s brain that cannot yet process the “newness” of a medium: “[N]ew media devices and artifacts themselves produce the sensations of a destabilizing surge of information or signal when they come into contact with a worldview of technics that has no affordances for them. […] New media are glitches by virtue of the forms this newness takes.”37

So what if the seemingly faulty or immoral ads in American Psycho (2012) are not glitches at all, but show us a future, where Kaplan’s “creolization” (in his use of the term, natural languages incorporating “linguistic biases of algorithms and the economical constraints of the global linguistic economy”)38 has already happened – and our contemporary semantic reading habits are just not adapted to it yet?

MEDIA POETICS AND INTERFACE-SPECIFIC LITERATURE

Cloud-based writing technologies are ephemeral: Google discontinued the algorithmic assessment of emails in 2017,39 but in contrast to locally installed software, which can still be accessed and researched on old PC’s, cloud-based software is forever lost to the researcher. The book American Psycho (2012) then just may as well be one of the few pieces of evidence we have on how the algorithm in Gmail worked in the year 2012.

American Psycho thus not only marks a specific point in the genealogy of writing, which is ever more difficult to trace due to the permanent stream of updates, bug fixes, add-ons or discontinuation of services; but is also a contribution to what Lori Emerson has called media poetics – writer’s engagements with their respective writing technologies –, the literary correspondent of media archaeology. For the 21st century she identifies “a practice not just of experimenting with the limits and possibilities of writing interfaces but rather of readingwriting: the practice of writing through the network, which as it tracks, indexes, and algorithmises every click and every bit of text we enter into the network, is itself constantly reading our writing and writing our reading.”40

American Psycho may then herald a specific subgenre of readingwriting, which by feeding canonical literary works into writing interfaces, reverse-engineers these technologies, rendering visible the opaque workings of the black box in the difference between pretext and new text.41 Operationalizing glitches, authors of such texts more resemble bug hunters or beta-testers than traditional writers, identifying the not-yet-perfect workings of a machine, but then, instead of writing a report or making suggestions for improvement, they use the book/novel as defamiliarising tool to illustrate their findings.42 This subgenre – or what could be called a version-specific, interface-specific literature – not only “addresses” or “questions” writing technologies but makes a direct claim to comparative analysis. It radicalizes Emerson’s notion of media poetics as media archaeology, as in American Psycho with the juxtaposition of canonical pretext and algorithmically mediated new text a way of literary comparison is offered, that lets the reader directly reflect on the workings of a blackboxed digital writing technology.

With cloud-based writing software increasingly also taking into account place, time, browser history, user profile, etc. and changes in the algorithm go unnoticed by users and even developers,43 the notion that interface critique can only be version critique44 is further complicated – each use of the algorithm being potentially singular and results impossible to reproduce. In the end, American Psycho thus of course cannot explain, how the Gmail-algorithm “really” works.45 But it explores how one can experimentally generate any knowledge about black boxes – and how this knowledge can be made tangible for human readers by using literature as a familiar mode of representation.

CODA: THE (WRITING) TECHNOLOGY OF THE SELF

If we return to Friedrich Nietzsche’s remark that writing tools affect our thinking, it appears as if in the case of digital writing technologies and algorithmic black boxes we increasingly cannot know how they influence our texts and how interfaces co-determine what is written (and thought). With the enmeshing of writing technologies with all areas of life – just think of what one does with the PC/smartphone, before/while/after one writes: book flights, communicate with friends, send money –, in the digital age, Foucault’s écriture de soi becomes a default, exploitable and heteronomous act – a “technology of the self” in the truest sense of the word:46 We are all like Patrick Bateman (minus the murder), portrayed and defined by opaque always-on algorithms with personalized constellations of products around us.

In his essay on “linguistic capitalism” Kaplan concludes that new tools must be developed to observe the current developments of algorithmically mediated language.47 – And if literature always also reflects on its technical conditions of possibility, why shouldn’t these “new tools” be works of interface-specific readingwriting like American Psycho (2012), tools that open up fresh perspectives on the contemporary revolution of writing and language?48

References

Bajohr, Hannes, Halbzeug. Textverarbeitung (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2018).

Cabell, Mimi, and Jason Huff, American Psycho (Vienna: Traumawien, 2012).

Crawford, Kate, A.I.’s White Guy Problem. The New York Times (June 25, 2016); https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/opinion/sunday/artificial-intelligences-white-guy-problem.html, access October 20, 2018, 9 pm.

Dastin, Jeffrey, Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters (October 10, 2018); https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight/amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK08G, access October 20, 2018.

Ellis, Bret Easton, American Psycho (New York: Vintage, 1991).

Emerson, Lori, Reading Writing Interfaces (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2014).

Flender, Karl Wolfgang, #nofilter. Self-narration, identity construction and metastorytelling in Snapchat, in: Interface Critique, ed. Florian Hadler and Joachim Haupt (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2016), p. 163–179.

Foucault, Michel, Ästhetik der Existenz. Schriften zur Lebenskunst (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 2007).

Foucault, M., Technologien des Selbst, in: Technologien des Selbst, ed. Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patrick H. Hutton (Frankfurt/Main: S. Fischer, 1993), pp. 24–62.

Galloway, Alexander R., Black Box, Black Bloc. A lecture given at the New School in New York City on April 12, 2010; http://cultureandcommunication.org/galloway/pdf/Galloway,%20Black%20Box%20Black%20Bloc,%20New%20School.pdf, access August 8, 2018.

Google, Ads in Gmail and your personal data. Gmail Help, April 8, 2011; https://web.archive.org/web/20110511094215/http://mail.google.com/support/bin/answer.py?answer=6603, access October 2, 2018, 7 pm.

Google, How Gmail ads work. Gmail Help; https://support.google.com/mail/answer/6603?hl=en, access September 9, 2018, 8 pm.

Hayles, N. Katherine, Human and Machine Cultures of Reading: A Cognitive-Assemblage Approach, PMLA 133/5 (2018), pp. 1225–1242.

Jones, Nathan, Glitch Poetics. The Posthumanities of Error, in: The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, ed. Joseph Tabbi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), pp. 237–252.

Kaplan, Frederic, Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation. Representations 127/1 (2014), pp. 57–63.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew, Tweet (2018). https://twitter.com/mkirschenbaum/status/1051649868241006597, access October 20, 2018, 8pm.

Kittler, Friedrich, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, transl. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

Manovich, Lev, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

Marczewska, Kaja, Erasing in the algorithmic extreme: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff’s American Psycho. Media-N Journal 11/1 (2015); http://median.newmediacaucus.org/the_aesthetics_of_erasure/erasing-in-the-algorithmic-extreme-mimi-cabell-and-jason-huffs-american-psycho, access August 15, 2018, 8 pm.

Menkman, Rosa, The Glitch Moment(um) (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011).

Nietzsche, Friedrich, Briefwechsel. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 1986).

Nietzsche, F., Sämtliche Briefe. Kritische Studienausgabe in 8 Bänden, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (München, Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 1986).

Passig, Kathrin, Fünfzig Jahre Blackbox. Merkur Blog (2017); https://www.merkur-zeitschrift.de/2017/11/23/fuenfzig-jahre-black-box, access June 15, 2018, 9 pm.

Stingelin, Martin, “UNSER SCHREIBZEUG ARBEITET MIT AN UNSEREN GEDANKEN.” Die poetologische Reflexion der Schreibwerkzeuge bei Georg Christoph Lichtenberg und Friedrich Nietzsche, in: Schreiben als Kulturtechnik, ed. Sandro Zanetti (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2012), p. 283–304.

Thom, René, Mathematical Models of Morphogenesis (Chichester: Prentice Hall, 1984).

Tonnard, Elisabeth, ”Speak! eyes En zie! (Gent: Druksel, 2010).

Weichbrodt, Gregor, On the Road (Berlin: 0x0a, 2014).

Footnotes

1 Nietzsche to Heinrich Köselitz, end of February 1882, in: Friedrich Nietzsche, Sämtliche Briefe. Kritische Studienausgabe in 8 Bänden, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (Munich, Berlin, New York 1986), vol. 6, no. 202, p. 172, quoted from Martin Stingelin, “UNSER SCHREIBZEUG ARBEITET MIT AN UNSEREN GEDANKEN.”, in: Schreiben als Kulturtechnik, ed. Sandro Zanetti (Berlin 2012), pp. 283–304, here p. 304. English transl.: “Our writing tools are also working on our thoughts”, here taken from Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, transl. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford 1999), p. 200.

2 Heinrich Köselitz to Nietzsche on February 19th 1882, in: Friedrich Nietzsche, Briefwechsel. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (Berlin, New York 1986), third devision, vol. 2, no. 107, p. 229, quoted from Stingelin, SCHREIBZEUG, p. 302. English transl.: “Both the distinctness of the letters, yet even more the markedness of your slogans surprised me. Maybe you even will adapt a whole new expression through use of this tool.” (My transl.)

3 Davide Giuratio, Martin Stingelin and Sandro Zanetti have mapped out the area of research on the genealogy of writing and the “scene of writing” (“Schreibszene”, developed from Rüdiger Campe’s model) and contributed seminal publications. Stingelin, SCHREIBZEUG mentions the examples of Goethe and Lichtenberg.

4 Lori Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces (Minneapolis 2014), p. ix.

5 Ibid.

6 Alexander Galloway defines the blackbox as “an opaque technological device for which only the inputs and outputs are known.” (Alexander R. Galloway, Black Box, Black Bloc. A lecture given at the New School in New York City on April 12, 2010; http://cultureandcommunication.org/galloway/pdf/Galloway,%20Black%20Box%20Black%20Bloc,%20New%20School.pdf, access August 8, 2018, 11 pm)

7 Stingelin, SCHREIBZEUG, p. 293.

8 Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces, p. xvii.

9 Social media writing tools such as Facebook, Twitter or Snapchat, whose interfaces each affect respective forms of writing, storytelling and identity construction shall not be the topic of this article. For an analysis of the Snapchat-interface see for instance Karl Wolfgang Flender, #nofilter. Self-narration, identity construction and metastorytelling in Snapchat, in: Interface Critique, ed. Florian Hadler and Joachim Haupt (Berlin 2016), pp. 163–179.

10 Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho (New York 1991), p. 3.

11 Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho (Vienna 2012), p. 3.

12 René Thom, Mathematical Models of Morphogenesis (Chichester 1984), p. 298.

13 The PDF is available on http://traumawien.at/prints/american-psycho/american_psycho_content.pdf, access October 1, 2018, 6:30 pm.

14 Not surprisingly a novel set in Manhattan is full of ads by New York companies. Yet four times ads by firms from New England appear without any reference of the region in the text. Upon my inquiry Cabell and Huff confirmed, that during producing American Psycho they actually were based in New England, so one might conclude that the appearance of the ads is actually also connected to the IP-address. – The 2012 Google Ad Policy however keeps quiet about using IPs for placement of relational ads. Compare Cabell and Huff, American Psycho, pp. 171, 179, 269 and 360.

15 The “Whitestrips Coupons” can also be read as an uncanny self-reflexive allusion to a text that is “stripped white”, inviting the reader to reflect whether this ad really is the output of the algorithm or might be a sign of the authors’ intentional interference.

16 Cabell and Huff, American Psycho, p. 57.

17 Ibid., pp. 257–258.

18 Ibid., pp. 281–282.

19 Ibid., p. 22.

20 Ibid., p. 180. It is striking, that this advertisement – in a telling parallel to the algorithmic remediation of the whole American Psycho – also advertises a process of translation/conversion/digitization, making this just one of many too-good-to-be-true ‘coincidences’, worthy of further interpretation, which appear throughout the book.

21 Frederic Kaplan, Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation. Representations 127/1 (2014), pp. 57–63.

22 Ibid., p. 59.

23 The keyword-sensitivity here obviously is not yet perfect, but of course the more the program is used, the more sophisticated it gets, as Google’s auctioning-algorithm is of course refined with every search, a match of keyword and ad positively evaluated if clicked-on, refining the algorithm’s “understanding” of language through feedback loops.

24 Cabell and Huff, American Psycho, p. 21.

25 Ibid., p. 105.

26 Ibid., p. 334.

27 Comparing the two instantiations, the differing page number and the differently aligned text are apparent. As the text progresses, the layout of American Psycho (2012) more and more detaches itself from the “original”, probably because of the different size of font and the automatic alignment versus the typesetting “by hand” in the original.

28 Cabell and Huff, American Psycho, p. 174. I put the ads from the footnotes in brackets. Quoted after the PDF-version, in which it is possible to make the whitened-out text visible (compare fig. 5).

29 Google, Ads in Gmail and your personal data. Gmail Help, April 8, 2011; https://web.archive.org/web/20110511094215/http://mail.google.com/support/bin/answer.py?answer=6603, access October 2, 2018, 7 pm.

30 Ibid.

31 See N. Katherine Hayles’ recent article in PMLA for a broad discussion of how machines and humans read differently, one of her key points being that “whereas reading and narrative are closely linked for humans, reading and correlation have a strong connection for machines.” (p. 1229) One can also argue that the two versions of American Psycho correspond with the difference between database and narrative. According to Lev Manovich, the database “represents the world as a list of items and it refuses to order this list. In contrast, a narrative creates a cause-and-effect trajectory of seemingly unordered items (events).” (p. 225) Cabell’s and Huff’s use of a narrative text to access the Google-AdWords-database, then comes into light as “the construction of an interface to a database.” (p. 226) This user interface is the text of the new American Psycho (2012). Comp. N. Katherine Hayles, Human and Machine Cultures of Reading: A Cognitive-Assemblage Approach, PMLA 133/5 (2018), pp. 1225–1242; Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA 2001).

32 Cabell and Huff imitate Google’s instrumental attitude toward text: “They reduce Ellis’ text to data, and reading and writing experience into an exercise in data mining and user profiling.” (Kaja Marczewska, Erasing in the algorithmic extreme: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff’s American Psycho. Media-N Journal 11 [1] (2015); http://median.newmediacaucus.org/the_aesthetics_of_erasure/erasing-in-the-algorithmic-extreme-mimi-cabell-and-jason-huffs-american-psycho, access August 15, 2018, 8 pm.)

33 Compare for example Kate Crawford, A.I.’s White Guy Problem. The New York Times (June 25, 2016); https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/opinion/sunday/artificial-intelligences-white-guy-problem.html, access October 20, 2018, 9 pm; Jeffrey Dastin, Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters (October 10, 2018); https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight/amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK08G, access October 20, 2018.

34 Rosa Menkman, The Glitch Moment(um) (Amsterdam 2011), p. 11.

35 Nathan Jones, Glitch Poetics. The Posthumanities of Error, in: The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, ed. Joseph Tabbi (London 2018), pp. 237–252, here S. 238, my emphasis.

36 Ibid., p. 239.

37 Ibid., p. 238.

38 Kaplan, Linguistic Capitalism, p. 61.

39 “We will not scan or read your Gmail messages to show you ads”, it now says on Google’s support page. “The process of selecting and showing personalized ads in Gmail is fully automated. These ads are shown to you based on your online activity while you're signed into Google.” In the face of today’s user-tracking the keyword analysis of 2012 as displayed in American Psycho seems almost innocent. (Google, How Gmail ads work. Gmail Help; https://support.google.com/mail/answer/6603?hl=en, access September 9, 2018, 8 pm.)

40 Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces, p. xiv.

41 Further examples would be Hannes Bajohr’s defamiliarisation of canonical German poems using the synonym-function in Microsoft Word (Hannes Bajohr, Halbzeug. Textverarbeitung [Berlin 2018], pp. 86–97), Elisabeth Tonnard's compressing canonical texts like Hamlet with Word’s AutoSummarize-tool (Elisabeth Tonnard, “Speak! eyes En zie! [Gent 2010]), or Gregor Weichbrodt feeding Kerouac’s On The Road into the Google Route planner, resulting in a contemporary road novel: “Head northwest on W 47th St toward 7th Ave. Take the 1st left onto 7th Ave. Turn right onto W 39th St. Take the ramp onto Lincoln Tunnel. Parts of this road are closed Mon–Fri 4:00 – 7:00 pm. Entering New Jersey.” (Gregor Weichbrodt, On the Road [Berlin 2014], p. 9).

42 Emerson has pointed to what could be called a respecification of the book in the digital age: “Perhaps, the future of digital literature is readingwriting that is born of the network but lives offline – digital literature transformed into bookbound readingwriting that performs and embodies its own frictional media archaeological analysis.” (Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces, p. 184.)

43 Recently it seems like a must for developers to attest their algorithms an own agency and non-intelligibility – catchwords: machine learning und neural networks –, yet this rhetorical blackboxing is nothing new, as programmer’s have said the same about their software half a century ago, as Kathrin Passig has shown. Andersen and Pold have also pointed to the importance of dismantling interface myths in Interface Critique vol. 1. (Kathrin Passig, Fünfzig Jahre Blackbox. Merkur Blog [2017]; https://www.merkur-zeitschrift.de/2017/11/23/fuenfzig-jahre-black-box, access June 15, 2018, 9 pm.)

44 Flender, #nofilter, p. 164.

45 The design of the printed book hints at this: With the original cover photograph removed, the book as object is itself a black box (see fig. 2). One could interpret the circle on the cover as a peephole, which allows a glimpse under the surface of the blackbox: But it affords no clear sight, just a shade of grey.

46 Michel Foucault, Ästhetik der Existenz. Schriften zur Lebenskunst (Frankfurt/Main 2007), and Michel Foucault, Technologien des Selbst, in: Technologien des Selbst, ed. Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patrick H. Hutton (Frankfurt/Main 1993), pp. 24–62.

47 Kaplan, Linguistic Capitalism, p. 62.

48 New technologies then of course call for new texts. Gmail has just introduced SmartReply, a function which automatically answers emails and already accounts for 11% of Gmail-traffic according to Google. So who will take Goethes Werther, feed it into Gmail, and write a reverse-engineered epistolary novel revealing the techné of this tool? (Matthew Kirschenbaum has entertained a similar thought in a tweet: https://twitter.com/mkirschenbaum/status/1051649868241006597, access October 20, 2018, 8pm.)

AMERICAN PSYCHO. READING AN ALGORITHM IN REVERSE

Karl Wolfgang Flender

Suggested citation: Flender, Karl Wolfgang (2019). “American Psycho. Reading an Algorithm in Reverse.” In: Interface Critique Journal 2. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang.

DOI: 10.11588/ic.2019.2.66992

This article is released under a

Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).

Karl Wolfgang Flender is a Ph.D. student at the Friedrich Schlegel Graduate School for Literary Studies at Freie Universität Berlin, investigating the interrelation of technology and knowledge in contemporary, experimental book-based literature. Having studied Creative Writing at the University of Hildesheim, he has published two novels with DuMont publishing house, Greenwash, Inc. (2015) and Helden der Nacht (2018). In 2019/2020 he will be Visiting Scholar at Columbia University.

Selected Publications:

Karl Wolfgang Flender, Literary forkbombs. Interventionist Conceptual Writing in the Age of Amazon. In: Hyperrhiz. New Media Cultures 20, (2019). doi:10.20415/hyp/020.net01

Karl Wolfgang Flender, #nofilter. Self-narration, identity construction and metastorytelling in Snapchat, in: Interface Critique, ed. Florian Hadler and Joachim Haupt (Berlin 2016), pp. 163–179.

“Google recommends a pulse monitor while someone’s bleeding to death, or suggests skin tightening while Bateman makes sausage of a victim.”

INTRODUCTION

“UNSER SCHREIBZEUG ARBEITET MIT AN UNSEREN GEDANKEN”, Friedrich Nietzsche famously remarks on his use of the Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, a forerunner of the typewriter which was developed for the visually impaired.1 Originally acquired by the shortsighted philosopher because of his rather illegible handwriting, the machine began to slowly affect his writing and thinking. Alluding to Nietzsche’s new telegram style and the capital letters (the Writing Ball did not have miniscules), his assistant, Peter Gast alias Heinrich Köselitz, observes in a letter: “Sowohl von der Deutlichkeit der Lettern, noch mehr aber von der Kernigkeit der Sprüche war ich überrascht. […] Vielleicht gewöhnen Sie Sich mit diesem Instrument gar eine neue Ausdrucksweise an.”2

Examples in literary history are legion, that each writing tool yields new materialities of text, new forms of writing and ways of thinking: The pencil for example allowed Goethe to effortlessly jot down his nighttime-inspirations, while Georg Lichtenberg’s experimental use of the quill resulted in his famous Sudelbücher (if need be, the quill dipped into coffee instead of ink); Kerouac binge-wrote On the Road on his Underwood Portable, the typewriter also enabling the typographic experiments of the Concrete Poets – in poetological texts and literary experiments writers investigate their respective writing tools as the technical conditions of the possibility of literature.3

With the advent of the personal computer, digital writing tools and their increased enmeshment through cloud-services, we have entered a new epoch of writing, in which “the interfaces themselves and therefore their constraints are becoming ever more difficult to perceive”, as Lori Emerson has noted in Reading Writing Interfaces.4 She has shown how the complex workings of digital writing tools under their shiny graphical user interfaces (GUIs) have become less and less observable to users, let alone comprehensible, since input and output are seemingly disconnected through opaque algorithmical operations and paradigms of user-friendliness and intuitive design, while the possibility of user’s choice has been strategically limited by software companies.5 The everyday digital writing tools thus appear as closed-off black boxes to the users,6 ever increasing the writer’s dependence on the Eigensinn of his or her tools.7 Or, more drastically put, as Emerson concludes at one point: “[T]hey frame what can and cannot be said.”8

Just think of the automatic spellchecking in Microsoft Word, which does not disclose on grounds of which grammatical rules or dictionary this or that word is underlined; or the AutoCorrect-function of Apple, which almost unnoticeably capitalizes words or corrects mistakes, whether or not the user intended it. AutoComplete interferes with smartphone-messaging, when words are proposed on grounds of a statistical or stochastic body that has been trained on the user’s habits; search engines complete search terms to entire sentences, and therefore influence what is searched and thus found; not to mention the most complex language technologies such as Google Translate and its machine learning algorithms.9

While one can get quite weary of reiterating how writing today is subject to international surveillance and corporate control – and that conditions of literary production, distribution and reception are becoming ever more intertwined with commercial, political and power interests as these writing tools have become the widely accepted and unchallenged norm –, a range of contemporary literary experiments still serves as a fresh take to critically assess these tools.

Fig. 1: Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho, Cover.

Fig. 2: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho, Cover.

AMERICAN PSYCHO (2012): BLACK-BOX-TESTING OF AN ALGORITHM

“ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE”,10 are the first, Dante-channelling, words of Bret Easton Ellis’ infamous novel American Psycho, published by Vintage Books in 1991, in which the brand-obsessed investment banker and yuppie Patrick Bateman turns into a perverse mass murderer. The eponymous 2012 edition of the book however, released by the publishing collective Traumawien, and, judging by its cover, also written by Ellis, begins like this:

“Crest(r) Whitestrips Coupon, Save $10 Now on Crest(r) Whitestrips. Get Whiter Teeth for the Holidays! Coupons.3DWhite.com/Whitestrips!”11

At first glance, one merely seems to be holding a cheap bootleg, at some stage of the illegal copying process infested by advertisements, a spambook so to say: Jacket, half-title and typesetting imitate the original’s design and typography, the chapter titles are identical, yet the 408 pages of the 2012 edition are almost completely white, except for constellations of footnotes, in which said advertisements appear (see fig. 1–4). On closer examination however, American Psycho (2012) turns out to be the result of the creative (mis-)use of a contemporary writing technology, namely Google Mail, as if taking to heart that “[t]he only conceivable way of unveiling a black box, is to play with it.”12

Fig. 3: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho, p. 3.

Fig. 4: Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho, p. 3.

For their American Psycho, the artist duo Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff sent Ellis’ novel page by page between to Gmail-accounts to and fro, and saved the ad-banners which appeared in the graphical user interface of the mail program. These so-called “relational ads” are generated through algorithmic keyword analysis of the email’s text, as when signing up for Gmail one automatically agrees that all in- and outgoing mails will be analysed to serve personalized ads (“we are always looking for more ways to deliver you the most useful and relevant ads”, it says on Google’s support-page). Subsequently, Cabell and Huff annotated the novel page by page with the collected ads, placing footnotes behind each word that presumably triggered the respective ad – for example, an ad for the already mentioned “Whitestrips Coupons” would be placed behind “teeth”. Then Cabell and Huff erased the original text of the novel, leaving us with blank pages and constellations of footnotes.

To read American Psycho (2012), one can thus consult a copy of the original to compare pages (see fig. 3 and 4), or download the freely available PDF-version, in which the original text is not deleted but only “whitened out” and can easily be rendered visible – the authors clearly encouraging such a reading.13 One then encounters multiple processes of reading and writing constellated in American Psycho (2012) for the reader to decipher: Google’s algorithm has “read” – aka processed – the pretext page by page (input) and written the ads (output), Cabell and Huff have compared the output to the pretext and positioned the ads in footnotes: In a black-box-testing-spirit feeding a canonical novel into the writing technology Gmail, Cabell and Huff render visible the opaque workings of the algorithm in the discrepancy between pretext and new text.

As one starts to follow the algorithm through the book(s), one basically tries to get into the algorithm’s head: Why does this or that ad appear on this particular page? Where is the keyword that triggered it? Is there one – or is the output not only influenced by the text on the page, but by some other signals like IP-address or previous searches…?14 Furthermore, one starts to compare passages/keywords throughout the novel, which apparently triggered identical ads – the common denominator, at times impossible to find. This is only complicated by the fact that one already reads a human interpretation of the algorithm – Cabell and Huff placed the ads “by hand” –, so if ads seem to be arbitrarily attached to keywords the reader might start looking for more adequate keywords on the same page, or at times even presumes that strategic authorial intervention could be at play…15

Reading the new American Psycho in this manner, one thus reconstructs the authors’ process of composing the text, retraces the workings of Gmail’s algorithm, and at the same time reads a translation of a novel, famous for its portrayal of 1980s consumer culture, into a present whose consumer culture is dictated by online advertisement – all three ways of reading deeply intertwined with each other.

ALGORITHMIC ACTUALIZATION AND LITERACY IN LINGUISTIC CAPITALISM

Reading American Psycho (2012), it is astonishing how close to home the advertisements hit: If in the “original” there are page-long descriptions of Bateman’s frenemies’ suits, ads for clothes appear (“Dress Shirt – SALE $29.89 / 60% OFF Robert Talbott / Dress like a secret agent / Joseph Bank Mens Shirts / R Laurens: Secret Sale”);16 high-end audio equipment is praised when Bateman plays music; a two-pager about drinking water is accompanied by six ads for “LIFE Water Ionizers(tm)” or “Free Water Cooler Rental”,17 and last but not least, the notoriously recurring “Crest(r) Whitestrips Coupons” (on 81 out of 408 pages!), give away Bateman’s obsession for teeth (and/or Google’s fondness of bleaching-ads). Sometimes the algorithm even uncannily grasps the gist of a scene, for example when an “Instant Tenant Screening” and criminal checks are advertised, while Bateman is interrogated by a homicide detective.18

The conceptual match of pretext (a novel about consumer culture saturated with brands) and applied procedure (keyword-triggered algorithms to display ads), results in an awkwardly adequate actualization of American Psycho for the present, as of course all the products in the footnotes stem from the year 2012 and not from the 1980s. The absurdity of the breathless 2012 online-advertisement-sound seems at times to perfectly match the surface-fixated Bateman:

Luxurious Volume, Full Bodied Hair. Seriously High Style. A New Level Of Fullness, www. JohnFrieda.com / 479 Short Hair Pictures, Find inspiration for your next cut with our short hairstyle pictures., Short-Hairstyles.StyleBistro.com / Clip-On Hair Extensions / Face Tightening Secret / 60 years old … A must see. FlexEffect Facialbuilding / Get Soft, Natural Curls.19

As an effect of this actualization, interesting superpositions appear. While in the original Bateman programs his VHS-recorder to record The Patty Winters Show, in the new version mp3-players are offered – in general, so it seems, the most striking difference between 1991 and 2012 are not the advertised clothes, furniture or food, but the media change as it is heralded in this ad: “Tape To Digital Converter, Convert Any Cassette Tape To Digital MP3 In 3 Easy Steps! $59.95, www.CassetteToUSB.com.”20

Gmail’s ad-placement, as illustrated in American Psycho (2012), is an expression of what Frederic Kaplan calls “linguistic capitalism”, namely the current state of permanent algorithmic evaluation and commodification of linguistic material via language and writing technologies.21 With Google as example, Kaplan describes how the linguistic capital of accumulated search-entries is translated directly into revenue through algorithmic keyword-auctions: Each word or sentence that is entered into Google’s interface is auctioned in split seconds to advertisers, whose ads are then displayed in the results. Kaplan concludes: “Some words and expressions have therefore become commodities with different monetary values that can be ‘bought’ from Google. In some sense, Google has extended capitalism to language, transforming linguistic capital into money.”22

This is also the case with Gmail and American Psycho (2012): For each keyword that has triggered an ad, a price has been paid (which makes one wonder how much money Google earned from the 819 ads in the making of the book); each word has been awarded a price in the logic of “linguistic capitalism”: it is treated and calculated according to statistical bodies, regardless of its narrative or semantic context, clearly implying a different sort of reading and appreciation of text than we human readers are accustomed to.23 The configuration of both cultures of reading in one text highlights the threshold and/or transition from human to digital/machinic/algorithmic literacies – they “read” differently.

ALGORITHMIC MISMATCHING AND THE POLITICS OF THE ALGORITHM

Besides the succeeding actualizations, the most striking feature of the new American Psycho are the absurdities, inaccuracies and paradoxes that originate from the algorithmic mismatches of semantic content and respective ad. If there’s “salmon au lait” on a restaurant menu, Google proposes to “Learn French in 10 Days”;24 another time it is obviously misinterpreting “chow-chow” and offering “Cheap Cowhide”25 (which for the knowing reader almost seems like an uncanny premonition to the skinning of people which will occur later in the novel), or having – without apparent keyword – a PR-campaign from the present of 2012 intrude the equally catastrophy-ridden Eighties: “BP, Info about the Gulf of Mexico Spill Learn More about How BP is Helping., www.BP.com/ GulfOfMexicoResponse.”26

Fig 6: Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho, p. 174.

Fig 7: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho, p. 163.

As one continues reading the novel(s) and Bateman begins his spree of murder and rape, the algorithm’s disturbing indifference towards violence becomes apparent: During the detailed description of the slashing of a dog, porcelain knives, knife sharpeners and a haircut are advertised: “[H]e doesn’t see me pull out the knife (Kyocera Knives on sale), the sharpest one (Best Knive Sharpener), with the serrated edge (Yoshi Blades Official Site)”. And a few sentences later: “I push the serrated blade into its stomach and quickly slice open its hairless belly (Great Haircuts).”28 – If Google’s goal is to provide users “with ads that are useful and relevant to their interests”,29 for a mass murderer like Patrick Bateman that apparently works just fine.

The list could go on and on: Google serves instant soup-ads while Bateman cooks a woman’s head, or suggests anti-wrinkle-products while he skins his victims. During these passages, which are unbearable to read and were responsible for American Psycho’s temporary indexing in countries such as Germany, the algorithm displays a decided insensitivity towards the semantic content and context. Googles full-mouthed ad policy can only be counted as a sarcastic comment to these observations: “[W]e are careful about the types of content we serve ads against. For example, Google may block certain ads from running next to an email about catastrophic news. In addition, we will not show ads based on sensitive information, such as race, religion, sexual orientation, health, or sensitive financial categories.”30

The reader’s amusement, ambiguity or disturbance regarding Gmail’s ad-placements, are again effects of the relationship of two different kinds of reading and their playing against each other in the book: the sense-making, semantic reading of human recipients and the algorithm’s keyword-oriented “reading”, or processing, of text against a database of ads.31 American Psycho (2012) is thus a hybrid book: Produced according to the logic of an algorithm32 but published as a printed book, the familiar narrative genre of the novel is what makes the taken for granted workings of the blackboxed writing interface observable through defamiliarisation: Gmail’s “ignorance” towards violence and racism and its willingness to serve ads on top appear as part of the bigger picture that similar technologies have been and are used in the “fight against terror”, equally combing mails for keywords, or how self-learning algorithms used in predictive policing exhibit racist attitudes with real-life effects, how hiring-tools of tech companies disadvantage women, etc.33 The programmed, economic, and political dispositif of the algorithm remains necessarily opaque, but here it can be glimpsed in the literary.

A POETICS OF THE GLITCH

As we have seen, not the perfect match of text and ad that facilitate this scrutinizing reading but rather the inconsistencies, paradoxes and mismatches throughout American Psycho invite the reader to reflect on the workings of the algorithm. Operationalizing the faultiness of an unperfected writing tool, Cabell and Huff employ a poetics of the glitch. Glitch theorist Rosa Menkman explains that a glitch appears when any medium is brought “into a critical state of hypertrophy” that allows to “subsequently criticize its inherent politics.”34 American Psycho (2012) does just that. It oversaturates a novel, which is already brimming with brand names, with even more advertising, bringing it into an unreadable “state of hypertrophy” and testing the sensitivity of a technology with page-long descriptions of slaughter. This critique in the guise of literature not only allows to reflect, but also to make tangible the politics of the program, as Nathan Jones notes: “[A] glitch is a moment which gives propulsion into an unforeseen area of critical enquiry – allowing us to not only observe, but experience beneath a media surface.”35

Admittedly, it is difficult to distinguish where the glitch begins and ends, as not only the artist or the faulty software are responsible for the glitch, but also the recipients who experience something as glitchy, as “glitches only exist against human expectations. […] [A] glitch comes into being solely at this moment of transversal entanglement between human and technological systems.”36 That said, the hypertrophy and seeming immorality of Gmail’s algorithm as displayed in American Psycho may also merely be effects of a human reader’s brain that cannot yet process the “newness” of a medium: “[N]ew media devices and artifacts themselves produce the sensations of a destabilizing surge of information or signal when they come into contact with a worldview of technics that has no affordances for them. […] New media are glitches by virtue of the forms this newness takes.”37

So what if the seemingly faulty or immoral ads in American Psycho (2012) are not glitches at all, but show us a future, where Kaplan’s “creolization” (in his use of the term, natural languages incorporating “linguistic biases of algorithms and the economical constraints of the global linguistic economy”)38 has already happened – and our contemporary semantic reading habits are just not adapted to it yet?

MEDIA POETICS AND INTERFACE-SPECIFIC LITERATURE

Cloud-based writing technologies are ephemeral: Google discontinued the algorithmic assessment of emails in 2017,39 but in contrast to locally installed software, which can still be accessed and researched on old PC’s, cloud-based software is forever lost to the researcher. The book American Psycho (2012) then just may as well be one of the few pieces of evidence we have on how the algorithm in Gmail worked in the year 2012.

American Psycho thus not only marks a specific point in the genealogy of writing, which is ever more difficult to trace due to the permanent stream of updates, bug fixes, add-ons or discontinuation of services; but is also a contribution to what Lori Emerson has called media poetics – writer’s engagements with their respective writing technologies –, the literary correspondent of media archaeology. For the 21st century she identifies “a practice not just of experimenting with the limits and possibilities of writing interfaces but rather of readingwriting: the practice of writing through the network, which as it tracks, indexes, and algorithmises every click and every bit of text we enter into the network, is itself constantly reading our writing and writing our reading.”40

American Psycho may then herald a specific subgenre of readingwriting, which by feeding canonical literary works into writing interfaces, reverse-engineers these technologies, rendering visible the opaque workings of the black box in the difference between pretext and new text.41 Operationalizing glitches, authors of such texts more resemble bug hunters or beta-testers than traditional writers, identifying the not-yet-perfect workings of a machine, but then, instead of writing a report or making suggestions for improvement, they use the book/novel as defamiliarising tool to illustrate their findings.42 This subgenre – or what could be called a version-specific, interface-specific literature – not only “addresses” or “questions” writing technologies but makes a direct claim to comparative analysis. It radicalizes Emerson’s notion of media poetics as media archaeology, as in American Psycho with the juxtaposition of canonical pretext and algorithmically mediated new text a way of literary comparison is offered, that lets the reader directly reflect on the workings of a blackboxed digital writing technology.

With cloud-based writing software increasingly also taking into account place, time, browser history, user profile, etc. and changes in the algorithm go unnoticed by users and even developers,43 the notion that interface critique can only be version critique44 is further complicated – each use of the algorithm being potentially singular and results impossible to reproduce. In the end, American Psycho thus of course cannot explain, how the Gmail-algorithm “really” works.45 But it explores how one can experimentally generate any knowledge about black boxes – and how this knowledge can be made tangible for human readers by using literature as a familiar mode of representation.

CODA: THE (WRITING) TECHNOLOGY OF THE SELF

If we return to Friedrich Nietzsche’s remark that writing tools affect our thinking, it appears as if in the case of digital writing technologies and algorithmic black boxes we increasingly cannot know how they influence our texts and how interfaces co-determine what is written (and thought). With the enmeshing of writing technologies with all areas of life – just think of what one does with the PC/smartphone, before/while/after one writes: book flights, communicate with friends, send money –, in the digital age, Foucault’s écriture de soi becomes a default, exploitable and heteronomous act – a “technology of the self” in the truest sense of the word:46 We are all like Patrick Bateman (minus the murder), portrayed and defined by opaque always-on algorithms with personalized constellations of products around us.

In his essay on “linguistic capitalism” Kaplan concludes that new tools must be developed to observe the current developments of algorithmically mediated language.47 – And if literature always also reflects on its technical conditions of possibility, why shouldn’t these “new tools” be works of interface-specific readingwriting like American Psycho (2012), tools that open up fresh perspectives on the contemporary revolution of writing and language?48

References

Bajohr, Hannes, Halbzeug. Textverarbeitung (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2018).

Cabell, Mimi, and Jason Huff, American Psycho (Vienna: Traumawien, 2012).

Crawford, Kate, A.I.’s White Guy Problem. The New York Times (June 25, 2016); https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/opinion/sunday/artificial-intelligences-white-guy-problem.html, access October 20, 2018, 9 pm.

Dastin, Jeffrey, Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters (October 10, 2018); https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight/amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK08G, access October 20, 2018.

Ellis, Bret Easton, American Psycho (New York: Vintage, 1991).

Emerson, Lori, Reading Writing Interfaces (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2014).

Flender, Karl Wolfgang, #nofilter. Self-narration, identity construction and metastorytelling in Snapchat, in: Interface Critique, ed. Florian Hadler and Joachim Haupt (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2016), p. 163–179.

Foucault, Michel, Ästhetik der Existenz. Schriften zur Lebenskunst (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 2007).

Foucault, M., Technologien des Selbst, in: Technologien des Selbst, ed. Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patrick H. Hutton (Frankfurt/Main: S. Fischer, 1993), pp. 24–62.

Galloway, Alexander R., Black Box, Black Bloc. A lecture given at the New School in New York City on April 12, 2010; http://cultureandcommunication.org/galloway/pdf/Galloway,%20Black%20Box%20Black%20Bloc,%20New%20School.pdf, access August 8, 2018.

Google, Ads in Gmail and your personal data. Gmail Help, April 8, 2011; https://web.archive.org/web/20110511094215/http://mail.google.com/support/bin/answer.py?answer=6603, access October 2, 2018, 7 pm.

Google, How Gmail ads work. Gmail Help; https://support.google.com/mail/answer/6603?hl=en, access September 9, 2018, 8 pm.

Hayles, N. Katherine, Human and Machine Cultures of Reading: A Cognitive-Assemblage Approach, PMLA 133/5 (2018), pp. 1225–1242.

Jones, Nathan, Glitch Poetics. The Posthumanities of Error, in: The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, ed. Joseph Tabbi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), pp. 237–252.

Kaplan, Frederic, Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation. Representations 127/1 (2014), pp. 57–63.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew, Tweet (2018). https://twitter.com/mkirschenbaum/status/1051649868241006597, access October 20, 2018, 8pm.

Kittler, Friedrich, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, transl. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

Manovich, Lev, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

Marczewska, Kaja, Erasing in the algorithmic extreme: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff’s American Psycho. Media-N Journal 11/1 (2015); http://median.newmediacaucus.org/the_aesthetics_of_erasure/erasing-in-the-algorithmic-extreme-mimi-cabell-and-jason-huffs-american-psycho, access August 15, 2018, 8 pm.

Menkman, Rosa, The Glitch Moment(um) (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011).

Nietzsche, Friedrich, Briefwechsel. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 1986).

Nietzsche, F., Sämtliche Briefe. Kritische Studienausgabe in 8 Bänden, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (München, Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 1986).

Passig, Kathrin, Fünfzig Jahre Blackbox. Merkur Blog (2017); https://www.merkur-zeitschrift.de/2017/11/23/fuenfzig-jahre-black-box, access June 15, 2018, 9 pm.

Stingelin, Martin, “UNSER SCHREIBZEUG ARBEITET MIT AN UNSEREN GEDANKEN.” Die poetologische Reflexion der Schreibwerkzeuge bei Georg Christoph Lichtenberg und Friedrich Nietzsche, in: Schreiben als Kulturtechnik, ed. Sandro Zanetti (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2012), p. 283–304.

Thom, René, Mathematical Models of Morphogenesis (Chichester: Prentice Hall, 1984).

Tonnard, Elisabeth, ”Speak! eyes En zie! (Gent: Druksel, 2010).

Weichbrodt, Gregor, On the Road (Berlin: 0x0a, 2014).

Footnotes

1 Nietzsche to Heinrich Köselitz, end of February 1882, in: Friedrich Nietzsche, Sämtliche Briefe. Kritische Studienausgabe in 8 Bänden, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (Munich, Berlin, New York 1986), vol. 6, no. 202, p. 172, quoted from Martin Stingelin, “UNSER SCHREIBZEUG ARBEITET MIT AN UNSEREN GEDANKEN.”, in: Schreiben als Kulturtechnik, ed. Sandro Zanetti (Berlin 2012), pp. 283–304, here p. 304. English transl.: “Our writing tools are also working on our thoughts”, here taken from Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, transl. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford 1999), p. 200.

2 Heinrich Köselitz to Nietzsche on February 19th 1882, in: Friedrich Nietzsche, Briefwechsel. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (Berlin, New York 1986), third devision, vol. 2, no. 107, p. 229, quoted from Stingelin, SCHREIBZEUG, p. 302. English transl.: “Both the distinctness of the letters, yet even more the markedness of your slogans surprised me. Maybe you even will adapt a whole new expression through use of this tool.” (My transl.)

3 Davide Giuratio, Martin Stingelin and Sandro Zanetti have mapped out the area of research on the genealogy of writing and the “scene of writing” (“Schreibszene”, developed from Rüdiger Campe’s model) and contributed seminal publications. Stingelin, SCHREIBZEUG mentions the examples of Goethe and Lichtenberg.

4 Lori Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces (Minneapolis 2014), p. ix.

5 Ibid.

6 Alexander Galloway defines the blackbox as “an opaque technological device for which only the inputs and outputs are known.” (Alexander R. Galloway, Black Box, Black Bloc. A lecture given at the New School in New York City on April 12, 2010; http://cultureandcommunication.org/galloway/pdf/Galloway,%20Black%20Box%20Black%20Bloc,%20New%20School.pdf, access August 8, 2018, 11 pm)

7 Stingelin, SCHREIBZEUG, p. 293.

8 Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces, p. xvii.

9 Social media writing tools such as Facebook, Twitter or Snapchat, whose interfaces each affect respective forms of writing, storytelling and identity construction shall not be the topic of this article. For an analysis of the Snapchat-interface see for instance Karl Wolfgang Flender, #nofilter. Self-narration, identity construction and metastorytelling in Snapchat, in: Interface Critique, ed. Florian Hadler and Joachim Haupt (Berlin 2016), pp. 163–179.

10 Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho (New York 1991), p. 3.

11 Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho (Vienna 2012), p. 3.

12 René Thom, Mathematical Models of Morphogenesis (Chichester 1984), p. 298.

13 The PDF is available on http://traumawien.at/prints/american-psycho/american_psycho_content.pdf, access October 1, 2018, 6:30 pm.

14 Not surprisingly a novel set in Manhattan is full of ads by New York companies. Yet four times ads by firms from New England appear without any reference of the region in the text. Upon my inquiry Cabell and Huff confirmed, that during producing American Psycho they actually were based in New England, so one might conclude that the appearance of the ads is actually also connected to the IP-address. – The 2012 Google Ad Policy however keeps quiet about using IPs for placement of relational ads. Compare Cabell and Huff, American Psycho, pp. 171, 179, 269 and 360.

15 The “Whitestrips Coupons” can also be read as an uncanny self-reflexive allusion to a text that is “stripped white”, inviting the reader to reflect whether this ad really is the output of the algorithm or might be a sign of the authors’ intentional interference.

16 Cabell and Huff, American Psycho, p. 57.

17 Ibid., pp. 257–258.

18 Ibid., pp. 281–282.

19 Ibid., p. 22.

20 Ibid., p. 180. It is striking, that this advertisement – in a telling parallel to the algorithmic remediation of the whole American Psycho – also advertises a process of translation/conversion/digitization, making this just one of many too-good-to-be-true ‘coincidences’, worthy of further interpretation, which appear throughout the book.

21 Frederic Kaplan, Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation. Representations 127/1 (2014), pp. 57–63.

22 Ibid., p. 59.

23 The keyword-sensitivity here obviously is not yet perfect, but of course the more the program is used, the more sophisticated it gets, as Google’s auctioning-algorithm is of course refined with every search, a match of keyword and ad positively evaluated if clicked-on, refining the algorithm’s “understanding” of language through feedback loops.

24 Cabell and Huff, American Psycho, p. 21.

25 Ibid., p. 105.

26 Ibid., p. 334.

27 Comparing the two instantiations, the differing page number and the differently aligned text are apparent. As the text progresses, the layout of American Psycho (2012) more and more detaches itself from the “original”, probably because of the different size of font and the automatic alignment versus the typesetting “by hand” in the original.

28 Cabell and Huff, American Psycho, p. 174. I put the ads from the footnotes in brackets. Quoted after the PDF-version, in which it is possible to make the whitened-out text visible (compare fig. 5).

29 Google, Ads in Gmail and your personal data. Gmail Help, April 8, 2011; https://web.archive.org/web/20110511094215/http://mail.google.com/support/bin/answer.py?answer=6603, access October 2, 2018, 7 pm.

30 Ibid.

31 See N. Katherine Hayles’ recent article in PMLA for a broad discussion of how machines and humans read differently, one of her key points being that “whereas reading and narrative are closely linked for humans, reading and correlation have a strong connection for machines.” (p. 1229) One can also argue that the two versions of American Psycho correspond with the difference between database and narrative. According to Lev Manovich, the database “represents the world as a list of items and it refuses to order this list. In contrast, a narrative creates a cause-and-effect trajectory of seemingly unordered items (events).” (p. 225) Cabell’s and Huff’s use of a narrative text to access the Google-AdWords-database, then comes into light as “the construction of an interface to a database.” (p. 226) This user interface is the text of the new American Psycho (2012). Comp. N. Katherine Hayles, Human and Machine Cultures of Reading: A Cognitive-Assemblage Approach, PMLA 133/5 (2018), pp. 1225–1242; Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA 2001).

32 Cabell and Huff imitate Google’s instrumental attitude toward text: “They reduce Ellis’ text to data, and reading and writing experience into an exercise in data mining and user profiling.” (Kaja Marczewska, Erasing in the algorithmic extreme: Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff’s American Psycho. Media-N Journal 11 [1] (2015); http://median.newmediacaucus.org/the_aesthetics_of_erasure/erasing-in-the-algorithmic-extreme-mimi-cabell-and-jason-huffs-american-psycho, access August 15, 2018, 8 pm.)

33 Compare for example Kate Crawford, A.I.’s White Guy Problem. The New York Times (June 25, 2016); https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/opinion/sunday/artificial-intelligences-white-guy-problem.html, access October 20, 2018, 9 pm; Jeffrey Dastin, Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters (October 10, 2018); https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight/amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK08G, access October 20, 2018.

34 Rosa Menkman, The Glitch Moment(um) (Amsterdam 2011), p. 11.

35 Nathan Jones, Glitch Poetics. The Posthumanities of Error, in: The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, ed. Joseph Tabbi (London 2018), pp. 237–252, here S. 238, my emphasis.

36 Ibid., p. 239.

37 Ibid., p. 238.

38 Kaplan, Linguistic Capitalism, p. 61.

39 “We will not scan or read your Gmail messages to show you ads”, it now says on Google’s support page. “The process of selecting and showing personalized ads in Gmail is fully automated. These ads are shown to you based on your online activity while you're signed into Google.” In the face of today’s user-tracking the keyword analysis of 2012 as displayed in American Psycho seems almost innocent. (Google, How Gmail ads work. Gmail Help; https://support.google.com/mail/answer/6603?hl=en, access September 9, 2018, 8 pm.)

40 Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces, p. xiv.

41 Further examples would be Hannes Bajohr’s defamiliarisation of canonical German poems using the synonym-function in Microsoft Word (Hannes Bajohr, Halbzeug. Textverarbeitung [Berlin 2018], pp. 86–97), Elisabeth Tonnard's compressing canonical texts like Hamlet with Word’s AutoSummarize-tool (Elisabeth Tonnard, “Speak! eyes En zie! [Gent 2010]), or Gregor Weichbrodt feeding Kerouac’s On The Road into the Google Route planner, resulting in a contemporary road novel: “Head northwest on W 47th St toward 7th Ave. Take the 1st left onto 7th Ave. Turn right onto W 39th St. Take the ramp onto Lincoln Tunnel. Parts of this road are closed Mon–Fri 4:00 – 7:00 pm. Entering New Jersey.” (Gregor Weichbrodt, On the Road [Berlin 2014], p. 9).

42 Emerson has pointed to what could be called a respecification of the book in the digital age: “Perhaps, the future of digital literature is readingwriting that is born of the network but lives offline – digital literature transformed into bookbound readingwriting that performs and embodies its own frictional media archaeological analysis.” (Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces, p. 184.)

43 Recently it seems like a must for developers to attest their algorithms an own agency and non-intelligibility – catchwords: machine learning und neural networks –, yet this rhetorical blackboxing is nothing new, as programmer’s have said the same about their software half a century ago, as Kathrin Passig has shown. Andersen and Pold have also pointed to the importance of dismantling interface myths in Interface Critique vol. 1. (Kathrin Passig, Fünfzig Jahre Blackbox. Merkur Blog [2017]; https://www.merkur-zeitschrift.de/2017/11/23/fuenfzig-jahre-black-box, access June 15, 2018, 9 pm.)

44 Flender, #nofilter, p. 164.

45 The design of the printed book hints at this: With the original cover photograph removed, the book as object is itself a black box (see fig. 2). One could interpret the circle on the cover as a peephole, which allows a glimpse under the surface of the blackbox: But it affords no clear sight, just a shade of grey.

46 Michel Foucault, Ästhetik der Existenz. Schriften zur Lebenskunst (Frankfurt/Main 2007), and Michel Foucault, Technologien des Selbst, in: Technologien des Selbst, ed. Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patrick H. Hutton (Frankfurt/Main 1993), pp. 24–62.

47 Kaplan, Linguistic Capitalism, p. 62.