YOU, THE USERS

Kalli Retzepi

"Who controls an interface? It is certainly not the user, no matter how hard the corporate rhetoric insists on that.“

“You know, with millions of apps, Shortcut enables incredible possibilities for how you use Siri. Now, as you know, Siri is more than just a voice. Siri is working all the time in the background to make proactive suggestions for you even before you ask, and now with Shortcut, Siri can do so much more. So, for instance, let's say you order a coffee every morning at Phil's before you go to work. Well now, Siri can suggest right on your lock screen that you do that. You tap on it, and you can place the order right from there. Or if when you get to the gym you use Active to track workouts, well that suggestion will appear right on your lock screen. And this even works when you pull down into Search. You'll get great suggestions. Like say you're running late for a meeting, well Siri will suggest you text the meeting organizer. Or when you go to the movie, suggest that you turn on Do Not Disturb. That's just being considerate. And remind you to call grandma on her birthday.”

– excerpt from Apple's WWDC 2018 Keynote.1

Suggested citation: Retzepi, Kalli (2019). “You, the users.” In: Interface Critique Journal 2. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang.

DOI: 10.11588/ic.2019.2.66984

This article is released under a

Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).

Kalli Retzepi is a critical technologist, a designer and a graduate of the Media Lab at MIT. Her work explores the politics of digital interfaces, the narrative of the user and imagines new metaphors for the Web.

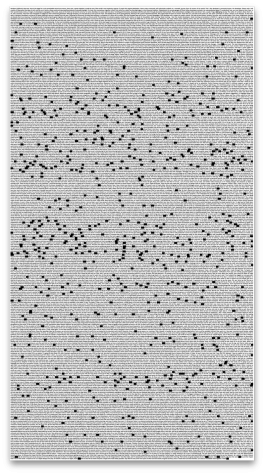

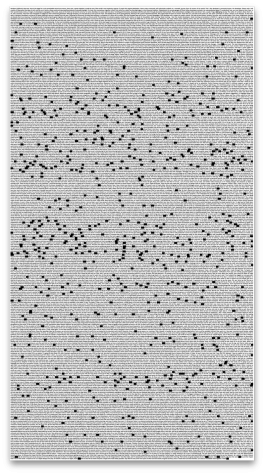

Text transcript of the entirety of Apple's WWDC 2018 Keynote event. Words like “you”, “yours” and “user” are highlighted in black. Permission of the author.

What rock concerts were in the sixties and seventies, tech keynotes are today. Big, mesmerizing, optimistic, glittering, confident, larger than life. Speakers, unsurprisingly mostly white and male, fluidly pace on big minimally decorated stages and elaborate with confidence on how their newly released product ameliorates – because that is of key importance – so many lives. Whose lives?

Yours, and mine. The users.

WHO IS THE USER?

The term "user" came into prominence in the post-1960s timeline of computation, where it was employed in the context of the then new concept of human-machine interface. The user is the human who interacts with the then grotesque mouse and keyboard, who points to the screen, who manipulates the state of a menu. The language employed from early on was conceived by engineers and was reductive but functional, often operationalised to fit problem-solving and task optimization paradigms.

Once the rough edges of human-machine interaction were sufficiently rounded by engineers, it looked like the user could take a lateral jump towards the field of design, but the inverse happened: the field of design constrained itself to fit into the vocabulary and mentality of the engineered user. Terms like "user-centered design" point to a certain willingness to talk design, but do so only in order to be heard by engineers and managers, solving for efficiency and comfort, formulating design in the computerized world as a means for optimisation. A certain vocabulary was built to cater to the needs of a user who is increasingly unaware of their role in a system that is built upon their choices, and is always hungry for more comfort and ease of mind. User-centered design, user experience, user retention, user engagement were elevated to a buzzword status in the post-dot.com era and ushered the world to a reality of screens constantly begging our attention, and vertical feeds that keep eyes and brains glued to their ethereally refreshing spinners.2

POLITICS OF THE USER

The vernacular of the user is, and should be treated as, political – not only because technology as a system is finding itself curiously now entangled with another system, that of Democracy – but because it has always been so. In addition to the well known fact that all of 20th century American computer science research and innovation was nurtured by Cold War scientific accelerationism, all of today’s tech giants can trace their beginnings to the movement of liberation, self-expression and self-reinvention whose origins are inextricably linked to and flow from that era in American politics.

The distance between hippies, with seemingly little respect and interest in the culture of capital and growth of economies, and their spiritual and often literal offspring, the tinkerers, dropouts and romantic failure seekers of Silicon Valley, is not as big as one would think. The main tenet in the 60’s ideology was that one is free to express themselves in any conceivable way, and subject themselves to as many transformative experiences as they wish – everything goes. So why stay the same? One should change. One should become better, in some vaguely defined way. Maybe happier? Definitely happier. That in limbo space of lifting one veil of selfhood and trying on another was often resolved by the help of drugs, which once Woodstock’s scent had left the air, gave their place to products and ritualistic behaviors: healthy eating, yoga retreats, meditation for the masses. And that also happened to coincide with college dropouts scavenging spare electronics parts and building futures in garages – the rest is history.

“On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like '1984'."

– Apple’s first commercial advertisement in 1984.3

What drugs were in the 1960’s, computers were in the 1980’s. Both could and did change lives – both required and defined a user, both rebooted one’s potential. Except only the latter were legal, and naturally positioned as products that someone needed to own to unlock the above promised potential. Of course, this potential is never really fulfilled, not until a newer and better version comes to our possession, resetting the clock of the excitement-expectation-let down cycle. With the establishment of Web, social media and particularly of the iPhone and smartphones, this became laughingly easy and trivial. Users were appearing left and right, fluidly rummaging through devices and habituating themselves to a life with a device glued to one extremity, dexterously untangling gordian knots of headphone cables.

In the winter of 2006, TIME magazine awarded their “Person of the Year” title to “You, the user”.4 Note the tone: “Yes, you. You control the Information Age. Welcome to your world”. Akin to the opening lines of this essay, it exemplifies the language that insidiously weaves a perfect bubble around us. Empowered and seemingly in control, the user is centered right in the middle of the web page, the screen, the action.

How does that then tie back to the main thesis of this essay, namely the gospelisation of tech rhetoric? Thorny issues of hyper-centralisation, opaqueness of data mining, surveillance and blind solutionism momentarily put aside, it matters because it scripts and enforces a very specific narrative between companies, developers, designers and users. And it matters doubly when the companies writing that narrative have reached well outside the borders of one country. Big tech companies have managed (albeit with less and less charisma) to not be dragged into the arena of today’s partisan politics by hiding in the shadow of libertarianism and sneering at the idea of a state, but while doing that, have acquired a dangerously close similarity to the state itself, and particularly its deeper parts, like the intelligence and the military.

In addition, and unlike most democratic states, they successfully operate and monitor multiple channels of information flow with their audience, except these channels are in most cases strictly unidirectional. The chain of commands that shape and launch products is without almost any exception a top down process driven by what generates more revenue, and that in most advertisement based models means maximizing the “time spent” with a product. Even if the developer or designer disagrees with a certain feature, they lack the incentive and infrastructure to voice opinion, knowing that if they don’t build it, then the next person will. Hyped and lavish Keynote events in this light seem but an empty promise and celebration to both the users as well as the developers – none of them have real agency over their role in the ecosystem. The former are passive consumers of experiences and the latter passive consumers of specs for these experiences.

THE ROLE OF THE INTERFACE

Branden Hookway writes: “The interface is not only the form and protocol by which communication and action occur between technology and user, but also the obligation for each to respond to the other”.5 That implies the existence, at least in theory, of a bidirectional flow of communication between the user and the technology, the two mutually shaped through friction with the interface.

Focusing on online interfaces, that used to be largely true before the dot.com era, when the Web belonged to amateurs who were building and linking its content slowly and often eccentrically, but with an immediate understanding and access to its underlying technology.6 When that started being taken away by complex templated websites and blogs rather than custom-made pages, interfaces started converging to each other and their users had to behave in ways that conformed to that trajectory. When Facebook first took off, one of its strongest features was its standardized and clean interface, akin to the privileged and guarded milieu from which it arose to prominence, which was an answer to the net chaos of its then rival MySpace, where anyone could have a profile, and style it to their liking.7

Interfaces mediate the boundary between a user and the information destined to reach them, and be generated from them. Who controls an interface? It is certainly not the user, no matter how hard the corporate rhetoric insists on that. On the contrary, users have no choice but to conform to the interface paradigms conceived and imposed to them. This is particularly evident in the cases of voice-controlled artificial intelligence agents used in households like Amazon’s Alexa. Instead of the interface being the facilitator of a fluid interactive performance between the information it embeds and the user, the inverse happens, with children saying their first words according to whether Alexa will respond to them.8 A bizarre power dynamic starts to take shape, where the user knows what they want to achieve, and they have no choice but to act in a particular way in order to work with the interface. They are treated thus as mechanistic rather than humanistic subjects, undoing the fundamental premise that an interface is there to be utilized by them, rather than condition them into certain behavioral paradigms.9

In addition, rigid interfaces and schemes of fraud empowerment habituate to certain forms of data input and thus their eventual hard-coding into collective memories. The equivalent of a book or a library for younger generations is without a doubt the Google search bar, parked at the same spot underneath the colorful child-like logo for the past twenty years. The only thing left for users to do in most cases is to passionately applaud or complain about the changes in visual and gestural design in their go-to interfaces, rarely effecting change.

YES, YOU SHOULD THINK

Ours are times of vivid criticism and faint critique. As designers, we need to move away from mentalities akin to “Don’t make me think” approaches to interface and systems design, and experiment with new interactive paradigms.10 As users, we ought to seriously reflect on how to position ourselves in a reality where convenience is our benevolent dictator.11 Increasing our tolerance and desire for abstraction and playful weirdness, just like the early Web net art projects were aiming to do, can awaken us to the tightly scripted role we have been handed by Silicon Valley’s cultureless race to the top.12 Artistic approaches like Lialina’s recent “Self-Portrait”,13 Rozendaal’s “Abstract Browsing”,14 Rafman’s “Nine Eyes of Google Street View”15 are intriguing and valuable because they undermine the concept of the ideal, helping us let go for a moment of any task oriented conventions.

Change does not only have to come from those distant to the tech ecosystem. While more and more engineers realize that ideologies can and do get encoded in products, interfaces and modes of interaction, they lack the means to effectively critique and control the consequences their work has on society. Silicon Valley’s culture of failure permissions the repeated effort but erases the consequence (Facebook’s “move fast and break things” pitch to fame) giving nor the time, neither the emotional and ethical bandwidth for someone to take a moment to step away and reflect on how their work influences society. Pushing for transparency, reevaluation of existing policies and tighter regulation could be effective ways to move forward, as has already started happening in some parts of the world.16

Superficial aesthetics should not continue to conceal the uneven distribution of power between the user, the interface and the information it mediates, no matter how sleek, small and fast the devices that surround us become. We need a new vocabulary for better articulating the roles of makers and consumers within the tech ecosystem. Technologists need to be incentivised and educated in order to meet practice with critique and theory. Designers and artists need to become more comfortable with unpacking and experimenting with the power dynamics embedded within the interface and its user. The user needs to be positioned as a truly sovereign subject vis-a-vis the interface, rather than a mechanistic “thing” with faux agency, conditioned to meet a certain set of specifications.17

No matter what Keynote events preach – we should be thinking.

References

Botsman, Rachel, Co–Parenting with Alexa. NYTimes Sunday Review (2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/07/opinion/sunday/children-alexa-echo-robots.html, access: September 20, 5:30pm.

Boyd, Danah, Viewing American class divisions through Facebook and MySpace. Apophenia Blog Essay (2007), http://www.danah.org/papers/essays/ClassDivisions.html, access: October 1, 2018, 8:30pm.

Chun, Wendy, Updating to Remain the Same. Habitual New Media (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2016).

Drucker, Johanna, Graphesis. Visual Forms of Knowledge Production (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2018).

Hookway, Branden, Interface (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2014).

Hormby, Tom, The Story Behind Apple’s 1984 Ad. (2014), http://lowendmac.com/2014/the-story-behind-apples-1984-ad/, access: October 8, 2018, 1:48pm.

Krug, Steve, Don't make me think. A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability (3rd Edition) (London: Pearson, 2014).

Lialina, Olia, A Vernacular Web. (2005), http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular/email/, access: September 4, 9:30pm.

Lialina, Olia, Self-Portrait. (2018), http://olia.lialina.work/, access: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

Rafman, Jon, Nine Eyes. (2008-ongoing), https://anthology.rhizome.org/9-eyes, access: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

Rozendaal, Rafaël, Abstract Browsing. (2015-ongoing), https://www.newrafael.com/notes-on-abstract-browsing/, access: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

Wu, Tim, The tyranny of convenience. NYTimes Sunday Review (2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/16/opinion/sunday/tyranny-convenience.html, access: October 2, 2018, 4:30pm.

https://anthology.rhizome.org/, accessed: October 4, 2018, 8:00pm.

https://www.apple.com/apple-events/june-2018/, access: October 4, 2018, 12:30pm.

http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,20061225,00.html, access: September 28, 2018, 2:00pm.

https://eugdpr.org/the-regulation/, access: October 8, 2018, 14:30pm.

Footnotes

1 Apple WWDC Special Event, Apple (2018); https://www.apple.com/apple-events/june-2018/, access: October 4, 2018, 12:30pm.

2 See Wendy Chun, Updating to Remain the Same. Habitual New Media (Cambridge MA 2016) p. 85.

3 Tom Hormby, The Story Behind Apple’s 1984 Ad (2014); http://lowendmac.com/2014/the-story-behind-apples-1984-ad/, access: October 8, 2018, 1:48pm.

4 TIME magazine Cover Archive (2006); http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,20061225,00.html, access: September 28, 2018, 2:00pm.

5 Branden Hookway, Interface (Cambridge, MA 2014), p. 7.

6 See Olia Lialina, A Vernacular Web (2005); http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular/email/, access: September 4, 9:30pm.

7 See Danah Boyd, Viewing American class divisions through Facebook and MySpace. Apophenia Blog Essay (2007); http://www.danah.org/papers/essays/ClassDivisions.html, access: October 1, 2018, 8:30pm.

8 See Rachel Botsman, Co–Parenting with Alexa. NYTimes Sunday Review (2017); https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/07/opinion/sunday/children-alexa-echo-robots.html, access: September 20, 5:30pm.

9 See Johanna Drucker, Graphesis. Visual Forms of Knowledge Production (Cambridge MA, 2018), p. 146.

10 See Steve Krug, Don't make me think. A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability (3rd Edition) (London 2014).

11 See Tim Wu, The tyranny of convenience. NYTimes Sunday Review (2018); https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/16/opinion/sunday/tyranny-convenience.html, access: October 2, 2018, 4:30pm.

12 See Rhizome, Net Art Anthology (2016 – present); https://anthology.rhizome.org/, accessed: October 4, 2018, 8:00pm.

13 Olia Lialina, Self-Portrait (2018); http://olia.lialina.work/, accessed: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

14 Rafaël Rozendaal, Abstract Browsing (2015-ongoing); https://www.newrafael.com/notes-on-abstract-browsing/, accessed: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

15 Jon Rafman, Nine Eyes (2008-ongoing); https://anthology.rhizome.org/9-eyes, accessed: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

16 See EU GDPR.ORG (2017); https://eugdpr.org/the-regulation/, accessed: October 8, 2018, 14:30pm.

17 See Wendy Chun, Updating to Remain the Same. Habitual New Media, Cambridge MA (2016) pp 84.

YOU, THE USERS

Kalli Retzepi

"Who controls an interface? It is certainly not the user, no matter how hard the corporate rhetoric insists on that.“

Suggested citation: Retzepi, Kalli (2019). “You, the users.” In: Interface Critique Journal 2. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang.

DOI: 10.11588/ic.2019.2.66984

This article is released under a

Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).

Kalli Retzepi is a critical technologist, a designer and a graduate of the Media Lab at MIT. Her work explores the politics of digital interfaces, the narrative of the user and imagines new metaphors for the Web.

“You know, with millions of apps, Shortcut enables incredible possibilities for how you use Siri. Now, as you know, Siri is more than just a voice. Siri is working all the time in the background to make proactive suggestions for you even before you ask, and now with Shortcut, Siri can do so much more. So, for instance, let's say you order a coffee every morning at Phil's before you go to work. Well now, Siri can suggest right on your lock screen that you do that. You tap on it, and you can place the order right from there. Or if when you get to the gym you use Active to track workouts, well that suggestion will appear right on your lock screen. And this even works when you pull down into Search. You'll get great suggestions. Like say you're running late for a meeting, well Siri will suggest you text the meeting organizer. Or when you go to the movie, suggest that you turn on Do Not Disturb. That's just being considerate. And remind you to call grandma on her birthday.”

– excerpt from Apple's WWDC 2018 Keynote.1

Text transcript of the entirety of Apple's WWDC 2018 Keynote event. Words like “you”, “yours” and “user” are highlighted in black. Permission of the author.

What rock concerts were in the sixties and seventies, tech keynotes are today. Big, mesmerizing, optimistic, glittering, confident, larger than life. Speakers, unsurprisingly mostly white and male, fluidly pace on big minimally decorated stages and elaborate with confidence on how their newly released product ameliorates – because that is of key importance – so many lives. Whose lives?

Yours, and mine. The users.

WHO IS THE USER?

The term "user" came into prominence in the post-1960s timeline of computation, where it was employed in the context of the then new concept of human-machine interface. The user is the human who interacts with the then grotesque mouse and keyboard, who points to the screen, who manipulates the state of a menu. The language employed from early on was conceived by engineers and was reductive but functional, often operationalised to fit problem-solving and task optimization paradigms.

Once the rough edges of human-machine interaction were sufficiently rounded by engineers, it looked like the user could take a lateral jump towards the field of design, but the inverse happened: the field of design constrained itself to fit into the vocabulary and mentality of the engineered user. Terms like "user-centered design" point to a certain willingness to talk design, but do so only in order to be heard by engineers and managers, solving for efficiency and comfort, formulating design in the computerized world as a means for optimisation. A certain vocabulary was built to cater to the needs of a user who is increasingly unaware of their role in a system that is built upon their choices, and is always hungry for more comfort and ease of mind. User-centered design, user experience, user retention, user engagement were elevated to a buzzword status in the post-dot.com era and ushered the world to a reality of screens constantly begging our attention, and vertical feeds that keep eyes and brains glued to their ethereally refreshing spinners.2

POLITICS OF THE USER

The vernacular of the user is, and should be treated as, political – not only because technology as a system is finding itself curiously now entangled with another system, that of Democracy – but because it has always been so. In addition to the well known fact that all of 20th century American computer science research and innovation was nurtured by Cold War scientific accelerationism, all of today’s tech giants can trace their beginnings to the movement of liberation, self-expression and self-reinvention whose origins are inextricably linked to and flow from that era in American politics.

The distance between hippies, with seemingly little respect and interest in the culture of capital and growth of economies, and their spiritual and often literal offspring, the tinkerers, dropouts and romantic failure seekers of Silicon Valley, is not as big as one would think. The main tenet in the 60’s ideology was that one is free to express themselves in any conceivable way, and subject themselves to as many transformative experiences as they wish – everything goes. So why stay the same? One should change. One should become better, in some vaguely defined way. Maybe happier? Definitely happier. That in limbo space of lifting one veil of selfhood and trying on another was often resolved by the help of drugs, which once Woodstock’s scent had left the air, gave their place to products and ritualistic behaviors: healthy eating, yoga retreats, meditation for the masses. And that also happened to coincide with college dropouts scavenging spare electronics parts and building futures in garages – the rest is history.

“On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like '1984'."

– Apple’s first commercial advertisement in 1984.3

What drugs were in the 1960’s, computers were in the 1980’s. Both could and did change lives – both required and defined a user, both rebooted one’s potential. Except only the latter were legal, and naturally positioned as products that someone needed to own to unlock the above promised potential. Of course, this potential is never really fulfilled, not until a newer and better version comes to our possession, resetting the clock of the excitement-expectation-let down cycle. With the establishment of Web, social media and particularly of the iPhone and smartphones, this became laughingly easy and trivial. Users were appearing left and right, fluidly rummaging through devices and habituating themselves to a life with a device glued to one extremity, dexterously untangling gordian knots of headphone cables.

In the winter of 2006, TIME magazine awarded their “Person of the Year” title to “You, the user”.4 Note the tone: “Yes, you. You control the Information Age. Welcome to your world”. Akin to the opening lines of this essay, it exemplifies the language that insidiously weaves a perfect bubble around us. Empowered and seemingly in control, the user is centered right in the middle of the web page, the screen, the action.

How does that then tie back to the main thesis of this essay, namely the gospelisation of tech rhetoric? Thorny issues of hyper-centralisation, opaqueness of data mining, surveillance and blind solutionism momentarily put aside, it matters because it scripts and enforces a very specific narrative between companies, developers, designers and users. And it matters doubly when the companies writing that narrative have reached well outside the borders of one country. Big tech companies have managed (albeit with less and less charisma) to not be dragged into the arena of today’s partisan politics by hiding in the shadow of libertarianism and sneering at the idea of a state, but while doing that, have acquired a dangerously close similarity to the state itself, and particularly its deeper parts, like the intelligence and the military.

In addition, and unlike most democratic states, they successfully operate and monitor multiple channels of information flow with their audience, except these channels are in most cases strictly unidirectional. The chain of commands that shape and launch products is without almost any exception a top down process driven by what generates more revenue, and that in most advertisement based models means maximizing the “time spent” with a product. Even if the developer or designer disagrees with a certain feature, they lack the incentive and infrastructure to voice opinion, knowing that if they don’t build it, then the next person will. Hyped and lavish Keynote events in this light seem but an empty promise and celebration to both the users as well as the developers – none of them have real agency over their role in the ecosystem. The former are passive consumers of experiences and the latter passive consumers of specs for these experiences.

THE ROLE OF THE INTERFACE

Branden Hookway writes: “The interface is not only the form and protocol by which communication and action occur between technology and user, but also the obligation for each to respond to the other”.5 That implies the existence, at least in theory, of a bidirectional flow of communication between the user and the technology, the two mutually shaped through friction with the interface.

Focusing on online interfaces, that used to be largely true before the dot.com era, when the Web belonged to amateurs who were building and linking its content slowly and often eccentrically, but with an immediate understanding and access to its underlying technology.6 When that started being taken away by complex templated websites and blogs rather than custom-made pages, interfaces started converging to each other and their users had to behave in ways that conformed to that trajectory. When Facebook first took off, one of its strongest features was its standardized and clean interface, akin to the privileged and guarded milieu from which it arose to prominence, which was an answer to the net chaos of its then rival MySpace, where anyone could have a profile, and style it to their liking.7

Interfaces mediate the boundary between a user and the information destined to reach them, and be generated from them. Who controls an interface? It is certainly not the user, no matter how hard the corporate rhetoric insists on that. On the contrary, users have no choice but to conform to the interface paradigms conceived and imposed to them. This is particularly evident in the cases of voice-controlled artificial intelligence agents used in households like Amazon’s Alexa. Instead of the interface being the facilitator of a fluid interactive performance between the information it embeds and the user, the inverse happens, with children saying their first words according to whether Alexa will respond to them.8 A bizarre power dynamic starts to take shape, where the user knows what they want to achieve, and they have no choice but to act in a particular way in order to work with the interface. They are treated thus as mechanistic rather than humanistic subjects, undoing the fundamental premise that an interface is there to be utilized by them, rather than condition them into certain behavioral paradigms.9

In addition, rigid interfaces and schemes of fraud empowerment habituate to certain forms of data input and thus their eventual hard-coding into collective memories. The equivalent of a book or a library for younger generations is without a doubt the Google search bar, parked at the same spot underneath the colorful child-like logo for the past twenty years. The only thing left for users to do in most cases is to passionately applaud or complain about the changes in visual and gestural design in their go-to interfaces, rarely effecting change.

YES, YOU SHOULD THINK

Ours are times of vivid criticism and faint critique. As designers, we need to move away from mentalities akin to “Don’t make me think” approaches to interface and systems design, and experiment with new interactive paradigms.10 As users, we ought to seriously reflect on how to position ourselves in a reality where convenience is our benevolent dictator.11 Increasing our tolerance and desire for abstraction and playful weirdness, just like the early Web net art projects were aiming to do, can awaken us to the tightly scripted role we have been handed by Silicon Valley’s cultureless race to the top.12 Artistic approaches like Lialina’s recent “Self-Portrait”,13 Rozendaal’s “Abstract Browsing”,14 Rafman’s “Nine Eyes of Google Street View”15 are intriguing and valuable because they undermine the concept of the ideal, helping us let go for a moment of any task oriented conventions.

Change does not only have to come from those distant to the tech ecosystem. While more and more engineers realize that ideologies can and do get encoded in products, interfaces and modes of interaction, they lack the means to effectively critique and control the consequences their work has on society. Silicon Valley’s culture of failure permissions the repeated effort but erases the consequence (Facebook’s “move fast and break things” pitch to fame) giving nor the time, neither the emotional and ethical bandwidth for someone to take a moment to step away and reflect on how their work influences society. Pushing for transparency, reevaluation of existing policies and tighter regulation could be effective ways to move forward, as has already started happening in some parts of the world.16

Superficial aesthetics should not continue to conceal the uneven distribution of power between the user, the interface and the information it mediates, no matter how sleek, small and fast the devices that surround us become. We need a new vocabulary for better articulating the roles of makers and consumers within the tech ecosystem. Technologists need to be incentivised and educated in order to meet practice with critique and theory. Designers and artists need to become more comfortable with unpacking and experimenting with the power dynamics embedded within the interface and its user. The user needs to be positioned as a truly sovereign subject vis-a-vis the interface, rather than a mechanistic “thing” with faux agency, conditioned to meet a certain set of specifications.17

No matter what Keynote events preach – we should be thinking.

References

Botsman, Rachel, Co–Parenting with Alexa. NYTimes Sunday Review (2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/07/opinion/sunday/children-alexa-echo-robots.html, access: September 20, 5:30pm.

Boyd, Danah, Viewing American class divisions through Facebook and MySpace. Apophenia Blog Essay (2007), http://www.danah.org/papers/essays/ClassDivisions.html, access: October 1, 2018, 8:30pm.

Chun, Wendy, Updating to Remain the Same. Habitual New Media (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2016).

Drucker, Johanna, Graphesis. Visual Forms of Knowledge Production (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2018).

Hookway, Branden, Interface (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2014).

Hormby, Tom, The Story Behind Apple’s 1984 Ad. (2014), http://lowendmac.com/2014/the-story-behind-apples-1984-ad/, access: October 8, 2018, 1:48pm.

Krug, Steve, Don't make me think. A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability (3rd Edition) (London: Pearson, 2014).

Lialina, Olia, A Vernacular Web. (2005), http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular/email/, access: September 4, 9:30pm.

Lialina, Olia, Self-Portrait. (2018), http://olia.lialina.work/, access: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

Rafman, Jon, Nine Eyes. (2008-ongoing), https://anthology.rhizome.org/9-eyes, access: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

Rozendaal, Rafaël, Abstract Browsing. (2015-ongoing), https://www.newrafael.com/notes-on-abstract-browsing/, access: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

Wu, Tim, The tyranny of convenience. NYTimes Sunday Review (2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/16/opinion/sunday/tyranny-convenience.html, access: October 2, 2018, 4:30pm.

https://anthology.rhizome.org/, accessed: October 4, 2018, 8:00pm.

https://www.apple.com/apple-events/june-2018/, access: October 4, 2018, 12:30pm.

http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,20061225,00.html, access: September 28, 2018, 2:00pm.

https://eugdpr.org/the-regulation/, access: October 8, 2018, 14:30pm.

Footnotes

1 Apple WWDC Special Event, Apple (2018); https://www.apple.com/apple-events/june-2018/, access: October 4, 2018, 12:30pm.

2 See Wendy Chun, Updating to Remain the Same. Habitual New Media (Cambridge MA 2016) p. 85.

3 Tom Hormby, The Story Behind Apple’s 1984 Ad (2014); http://lowendmac.com/2014/the-story-behind-apples-1984-ad/, access: October 8, 2018, 1:48pm.

4 TIME magazine Cover Archive (2006); http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,20061225,00.html, access: September 28, 2018, 2:00pm.

5 Branden Hookway, Interface (Cambridge, MA 2014), p. 7.

6 See Olia Lialina, A Vernacular Web (2005); http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular/email/, access: September 4, 9:30pm.

7 See Danah Boyd, Viewing American class divisions through Facebook and MySpace. Apophenia Blog Essay (2007); http://www.danah.org/papers/essays/ClassDivisions.html, access: October 1, 2018, 8:30pm.

8 See Rachel Botsman, Co–Parenting with Alexa. NYTimes Sunday Review (2017); https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/07/opinion/sunday/children-alexa-echo-robots.html, access: September 20, 5:30pm.

9 See Johanna Drucker, Graphesis. Visual Forms of Knowledge Production (Cambridge MA, 2018), p. 146.

10 See Steve Krug, Don't make me think. A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability (3rd Edition) (London 2014).

11 See Tim Wu, The tyranny of convenience. NYTimes Sunday Review (2018); https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/16/opinion/sunday/tyranny-convenience.html, access: October 2, 2018, 4:30pm.

12 See Rhizome, Net Art Anthology (2016 – present); https://anthology.rhizome.org/, accessed: October 4, 2018, 8:00pm.

13 Olia Lialina, Self-Portrait (2018); http://olia.lialina.work/, accessed: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

14 Rafaël Rozendaal, Abstract Browsing (2015-ongoing); https://www.newrafael.com/notes-on-abstract-browsing/, accessed: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

15 Jon Rafman, Nine Eyes (2008-ongoing); https://anthology.rhizome.org/9-eyes, accessed: October 9, 2018, 10:00am.

16 See EU GDPR.ORG (2017); https://eugdpr.org/the-regulation/, accessed: October 8, 2018, 14:30pm.

17 See Wendy Chun, Updating to Remain the Same. Habitual New Media, Cambridge MA (2016) pp 84.