1970:

AUTOMOBILE AND INFORMATION: THE SELF, THE AUTOMOBILE AND TECHNOLOGY

Max Bense

“[…] it is almost as if a new kind of existence had occured: the consciousness-like machine, the selflike automobile, a perfect human-machine team, an existential partnership between disturbances and fears, between mechanical actions and human reactions, between signals and impulses, noises and decisions.”

A self is not something that one has, but that one is. However one has an automobile and is not it, and hence the automobile has a self but is not one, and a self has an automobile but is not itself a car. This is a text about the difference between having and being, and this difference between having and being is also the difference between the car that drives and the self that drives it, but since that which drives can be both the car and the self, that which drives sublates the difference between self and car, and with this, the text about having and being, or car and self, becomes a text about driving, in which the car becomes the self, and the self the car.

A car is only a classical machine insofar as it produces energy and performs a task, like all classical machines. But it is also a ‘transclassical machine’ insofar as it processes data and produces communication, like all transclassical machines. As such, it necessarily belongs to the modern, advanced class of machines of data processing engines. The self that it has provides it with the data that it processes. The processing consists in the translation of the data provided by the self into the movements that the car delivers. Because it drives, the car is afforded the status of a place, a line, a kind of margin where the world and consciousness are continually clashing; we could also say: where being and thought clash. This is a motif from Hegelian metaphysics, and thus the car, or more precisely, its essential condition – namely movement – achieves the attractiveness of a metaphysical vehicle. Unintentionally, this makes the text about the difference between the self and the car into a technical text, and the technical text into a metaphysical one.

The car does not only move the self, it also moves the reflection of the self; that silent contour of thought relative to the noisy contour of driving. Undoubtedly, at the outset the silent contour of reflection precisely follows the noisy contour of driving; the self diligently follows the car; the thinking being is entirely fixated on the driving being. Only later, when the self has gradually adapted to the automobile, is the information provided which the car requires in order to be able to convert it into motion – automatically, without a thought, during the tender conversation with the girlfriend in the passenger seat about the flight to Madeira – suddenly everything seems to happen on its own. It becomes utterly evident that consciousness is in principal without place, does not constitute a substance, but rather a function, as old William James once put it. In that the thinking being becomes accustomed to the driving being, self and car melding increasingly into an almost surreal automaton – however with each also remaining separate and always continuing to signify independent entities to us, namely a driving being and a thinking being – it is almost as if a new kind of existence had occured: the consciousness-like machine, the self-like automobile, a perfect human-machine team, an existential partnership between disturbances and fears, between mechanical actions and human reactions, between signals and impulses, noises and decisions.

If one proceeds with this reflection, especially at increasing velocity, one quickly discovers that this double being of a driving self and acting car also possesses its difficulties between existential desire and worldly reason. The categorical imperative of moral action is continually endangered by the intimate experience of aesthetic desire. But since the sense of the world of this mechanical being can only be an artistic one, and all such artistry consists in the production of a total equilibrium between security and precision (security for the self and precision for the car), this very artistic sense of the world launches the double being of the car-self through the conflict between sensuous action and empirical desire. But if the moment of maximum velocity which realises the complete balance between precision and security has arrived, this difficult reflection must undoubtedly be abandoned. So let us abandon it.

Slowing down, the self discovers that it is simultaneously sitting and driving. However the driving being has irreparably damaged (if not demolished) the sense of settledness in the thinking being. Primarily through the car, the human being has taken on a tourist-like existence, and the principle of tourism has become a principle of existence. The placelessness of consciousness that is confirmed in the automobile also confirms the alterability of place for the body. Automobiles inhabit the cities as people do, and when people leave the cities, so do the automobiles. Through the car, the city has ceased to be a clear principle of settledness. The automobile-self demands the automobile-city and the automobile-street. Only here can human beings be in principle the stronger being, while in nature they will presumably always be the weaker being.

It is almost impossible to calculate just how many findings and innovations, how much scientific data, how many decisions about truthfulness and falsity were necessary to create the automobile, which therefore constitutes an immense reservoir of human knowledge, humanity’s capacity for creativity. If we consult Leibniz on the differentiation between human creativity and its divine counterpart, then “the all-powerful word Fiat” (as Leibniz formulated it) sufficed for divine creativity to create the world; while for human creativity, the creation of the automobile required a long chain of pleasure and pain, experiences and disappointments, decisions about the truthfulness and falsity of findings. But it is precisely the intelligence stored within it which makes the automobile into an being which is receptive of human intelligence.

Translated by Joel Scott

With kind permission by Elisabeth Walther-Bense (†)

Commentary

Max Bense’s 1970 essay, „Auto und Information. Das Ich, das Auto und die Technik“, which title is here translated as “Automobile and Information. The Self, the Automobile and Technology,” deals with a man-machine interaction common to most members of industrialized societies. Bense describes a relation between two entities as an interdependent one: man becoming a driver in the function of the machine, the machine becoming auto-mobile as a function of its driver. Bense emphatically outlines a techno-ontological relation which offers the man-machine interface paradigm in a nutshell – “the consciousness-like machine, the self-like automobile, a complete human-machine team”.

The essay was first published in the Swiss journal DU, vol. 30, in October 1970 and has been rereleased in the collected papers: Max Bense, Ausgewählte Schriften, vol. 4: Poetische Texte, ed. by Elisabeth Walther-Bense (Stuttgart and Weimar: Metzler, 1998). The English version published here has been translated from the German by Joel Scott. We would like to dedicate it to Max Bense’s wife and intellectual collaborator Elisabeth Walther-Bense who kindly granted us permission to translate and republish this wonderful analytical artefact that emphasizes a non-trivial relation between man and machine. Elisabeth Walther-Bense passed away on January 10, 2018 in Stuttgart at the age of 95 years.

- Daniel Irrgang

Suggested citation: Bense, Max (2018 [1970]). “The Self, the Automobile and Technology.” In Interface Critique Journal Vol.1. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang. DOI: 10.11588/ic.2018.0.44745

This article is released under a Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).

Max Bense † (1910 - 1990) was a German philosopher and writer in the fields of philosophy of science, aesthetics, and semiotics. He probably is best known for his work on text theory and information aesthetics, a field he established parallel to, although independently from, Abraham A. Moles. Bense taught philosophy of technology, science theory, and mathematical logic at the University of Stuttgart, where he became professor emeritus in 1978.

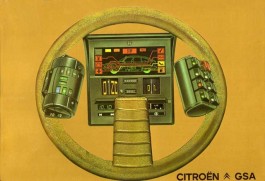

The image is taken from the user manual of a Citroën GSA, which came on the market around the same time as the essay was written and which was famous for its elaborated cockpit control elements (the image has been selected by the editors and is not part of the original publication).

1970:

AUTOMOBILE AND INFORMATION: THE SELF, THE AUTOMOBILE AND TECHNOLOGY

Max Bense

“[…] it is almost as if a new kind of existence had occured: the consciousness-like machine, the selflike automobile, a perfect human-machine team, an existential partnership between disturbances and fears, between mechanical actions and human reactions, between signals and impulses, noises and decisions.”

Translated by Joel Scott

With kind permission by Elisabeth Walther-Bense (†)

Commentary

Max Bense’s 1970 essay, „Auto und Information. Das Ich, das Auto und die Technik“, which title is here translated as “Automobile and Information. The Self, the Automobile and Technology,” deals with a man-machine interaction common to most members of industrialized societies. Bense describes a relation between two entities as an interdependent one: man becoming a driver in the function of the machine, the machine becoming auto-mobile as a function of its driver. Bense emphatically outlines a techno-ontological relation which offers the man-machine interface paradigm in a nutshell – “the consciousness-like machine, the self-like automobile, a complete human-machine team”.

The essay was first published in the Swiss journal DU, vol. 30, in October 1970 and has been rereleased in the collected papers: Max Bense, Ausgewählte Schriften, vol. 4: Poetische Texte, ed. by Elisabeth Walther-Bense (Stuttgart and Weimar: Metzler, 1998). The English version published here has been translated from the German by Joel Scott. We would like to dedicate it to Max Bense’s wife and intellectual collaborator Elisabeth Walther-Bense who kindly granted us permission to translate and republish this wonderful analytical artefact that emphasizes a non-trivial relation between man and machine. Elisabeth Walther-Bense passed away on January 10, 2018 in Stuttgart at the age of 95 years.

- Daniel Irrgang

Suggested citation: Bense, Max (2018 [1970]). “The Self, the Automobile and Technology.” In Interface Critique Journal Vol.1. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang. DOI: 10.11588/ic.2018.0.44745

This article is released under a Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).

Max Bense † (1910 - 1990) was a German philosopher and writer in the fields of philosophy of science, aesthetics, and semiotics. He probably is best known for his work on text theory and information aesthetics, a field he established parallel to, although independently from, Abraham A. Moles. Bense taught philosophy of technology, science theory, and mathematical logic at the University of Stuttgart, where he became professor emeritus in 1978.

A self is not something that one has, but that one is. However one has an automobile and is not it, and hence the automobile has a self but is not one, and a self has an automobile but is not itself a car. This is a text about the difference between having and being, and this difference between having and being is also the difference between the car that drives and the self that drives it, but since that which drives can be both the car and the self, that which drives sublates the difference between self and car, and with this, the text about having and being, or car and self, becomes a text about driving, in which the car becomes the self, and the self the car.

A car is only a classical machine insofar as it produces energy and performs a task, like all classical machines. But it is also a ‘transclassical machine’ insofar as it processes data and produces communication, like all transclassical machines. As such, it necessarily belongs to the modern, advanced class of machines of data processing engines. The self that it has provides it with the data that it processes. The processing consists in the translation of the data provided by the self into the movements that the car delivers. Because it drives, the car is afforded the status of a place, a line, a kind of margin where the world and consciousness are continually clashing; we could also say: where being and thought clash. This is a motif from Hegelian metaphysics, and thus the car, or more precisely, its essential condition – namely movement – achieves the attractiveness of a metaphysical vehicle. Unintentionally, this makes the text about the difference between the self and the car into a technical text, and the technical text into a metaphysical one.

The car does not only move the self, it also moves the reflection of the self; that silent contour of thought relative to the noisy contour of driving. Undoubtedly, at the outset the silent contour of reflection precisely follows the noisy contour of driving; the self diligently follows the car; the thinking being is entirely fixated on the driving being. Only later, when the self has gradually adapted to the automobile, is the information provided which the car requires in order to be able to convert it into motion – automatically, without a thought, during the tender conversation with the girlfriend in the passenger seat about the flight to Madeira – suddenly everything seems to happen on its own. It becomes utterly evident that consciousness is in principal without place, does not constitute a substance, but rather a function, as old William James once put it. In that the thinking being becomes accustomed to the driving being, self and car melding increasingly into an almost surreal automaton – however with each also remaining separate and always continuing to signify independent entities to us, namely a driving being and a thinking being – it is almost as if a new kind of existence had occured: the consciousness-like machine, the self-like automobile, a perfect human-machine team, an existential partnership between disturbances and fears, between mechanical actions and human reactions, between signals and impulses, noises and decisions.

If one proceeds with this reflection, especially at increasing velocity, one quickly discovers that this double being of a driving self and acting car also possesses its difficulties between existential desire and worldly reason. The categorical imperative of moral action is continually endangered by the intimate experience of aesthetic desire. But since the sense of the world of this mechanical being can only be an artistic one, and all such artistry consists in the production of a total equilibrium between security and precision (security for the self and precision for the car), this very artistic sense of the world launches the double being of the car-self through the conflict between sensuous action and empirical desire. But if the moment of maximum velocity which realises the complete balance between precision and security has arrived, this difficult reflection must undoubtedly be abandoned. So let us abandon it.

Slowing down, the self discovers that it is simultaneously sitting and driving. However the driving being has irreparably damaged (if not demolished) the sense of settledness in the thinking being. Primarily through the car, the human being has taken on a tourist-like existence, and the principle of tourism has become a principle of existence. The placelessness of consciousness that is confirmed in the automobile also confirms the alterability of place for the body. Automobiles inhabit the cities as people do, and when people leave the cities, so do the automobiles. Through the car, the city has ceased to be a clear principle of settledness. The automobile-self demands the automobile-city and the automobile-street. Only here can human beings be in principle the stronger being, while in nature they will presumably always be the weaker being.

It is almost impossible to calculate just how many findings and innovations, how much scientific data, how many decisions about truthfulness and falsity were necessary to create the automobile, which therefore constitutes an immense reservoir of human knowledge, humanity’s capacity for creativity. If we consult Leibniz on the differentiation between human creativity and its divine counterpart, then “the all-powerful word Fiat” (as Leibniz formulated it) sufficed for divine creativity to create the world; while for human creativity, the creation of the automobile required a long chain of pleasure and pain, experiences and disappointments, decisions about the truthfulness and falsity of findings. But it is precisely the intelligence stored within it which makes the automobile into an being which is receptive of human intelligence.

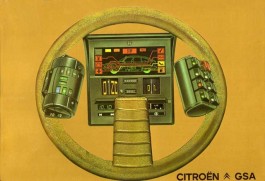

The image is taken from the user manual of a Citroën GSA, which came on the market around the same time as the essay was written and which was famous for its elaborated cockpit control elements (the image has been selected by the editors and is not part of the original publication).